What happens when we are all waiting at the same time?

Attila Tordai-S. in conversation with Larisa David

Larisa David, See Something Suspicious, 2018, from the group exhibition Tripping Autonomy, De Kroon, Rotterdam, Netherlands, photo by Tor Jonsson

Larisa David, Fangless, 2017, from the curatorial program Why Is Everybody Being So Nice?, De Appel, Amsterdam, Netherlands, photo by Carina Ederman

Attila Tordai-S.: Your proposal for the festival We Are All Emotional is a performance based on the question: “What happens when we are all waiting at the same time?” In the midst of the pandemic and in light of the restrictions currently imposed, this question is quite pertinent, and I would say the answer or answers are in front of our eyes. I mean, we see what is happening. When you asked yourself this question, did you have the concrete situation of the pandemic in mind, or it was this an older question of yours that you found appropriate to use now in the context of the lockdown?

Larisa David: Before the pandemic hit, I was waiting to get back on my feet after going through a difficult period, so I was no stranger to the theme of waiting. Of course, each of us has different experiences with waiting, and from my perspective, they are always personal. It’s about feeling powerless – you are vulnerable. During this period, with coronavirus, waiting has become more generalized. We have all experienced intense moments of disorientation, anxiety, and uncertainty while time stretched and prolonged with no end in sight. The degradation of work, job losses, lack of social protection, emotional and psychological fragility, and isolation have been intensified in this period, highlighting an already existing crisis in the history of capitalism. And then there’s grieving the loss of the future. So I felt like we were waiting together for this moment to pass. I wondered, if time is inescapable, how do we deal with this interval. I suspect that in such moments of suspension, we realize more than ever how connected we are and how much we need each other. From this perspective, waiting can be illuminated by hope and by the potential to imagine change. When I started asking myself what happens when we are all waiting at the same time, I soon realized that the question should be followed by other questions key to the performance: Are we even waiting for the same thing? Are we even waiting in the same way? What if while we are waiting, we prepare for the next event?

Attila: Does this preparation happen on a personal level or a more general or social level? Could you elaborate a bit about what you mean by “the next event”? Is it simply the future to come, or is the event you are referring to the unknown, with its complex forms of possible danger which require preparation and survival methodologies in order for us to defend ourselves?

Larisa: Waiting is usually seen as non-productive time, based on stagnation and lack of movement. As such, waiting can be experienced as a gap between events, so when I say “the next event,” I mean moving out of the gap and into a sense of action. I think for me personally, this interval has been about ways of shifting my perspective from “waiting something out” to “waiting for something.” I tried to bring meaning to this period by seeking people out and spending time with them. It’s nice to do nothing with someone. I hoped that this way I would alleviate some of the guilt I felt for not being productive, for not growing, making, doing, or even knowing where I am most of the time. This in turn makes me now reflect on forms of kinship that are relevant to me. But throughout all of this, the aspect of hope was important as it allowed me to reject passive resignation towards that which comes to me. It’s impossible for me to imagine the future, but I know it’s not the same future we imagined a year ago. What I can imagine is that we as a society will want new ways to reorient ourselves in a world that has changed on both a social and personal level. Even our understanding of “we” will probably change. So I think it’s important that when the waiting ends, we resist going back to normal.

Attila: One of your interests is exploring the relationship between visibility and invisibility, presence and absence. Do you see a redistribution of attention or a new balance between these notions now? How did you think of approaching these questions in the performance?

Larisa: One of the most interesting aspects for me is the relationship between the performer and the audience. This is the relationship that I am working with, trying to complicate and blur the boundaries of. I don’t want the audience to fade into the background, to be a neutral observer. Last year, the pandemic brought a lot of uncertainty to live performances, and I struggled to think about the performer while also considering that the audience might be absent. This made me think about other ways of working with text and performativity that were accessible to me while enclosed inside the walls of my home and studio.

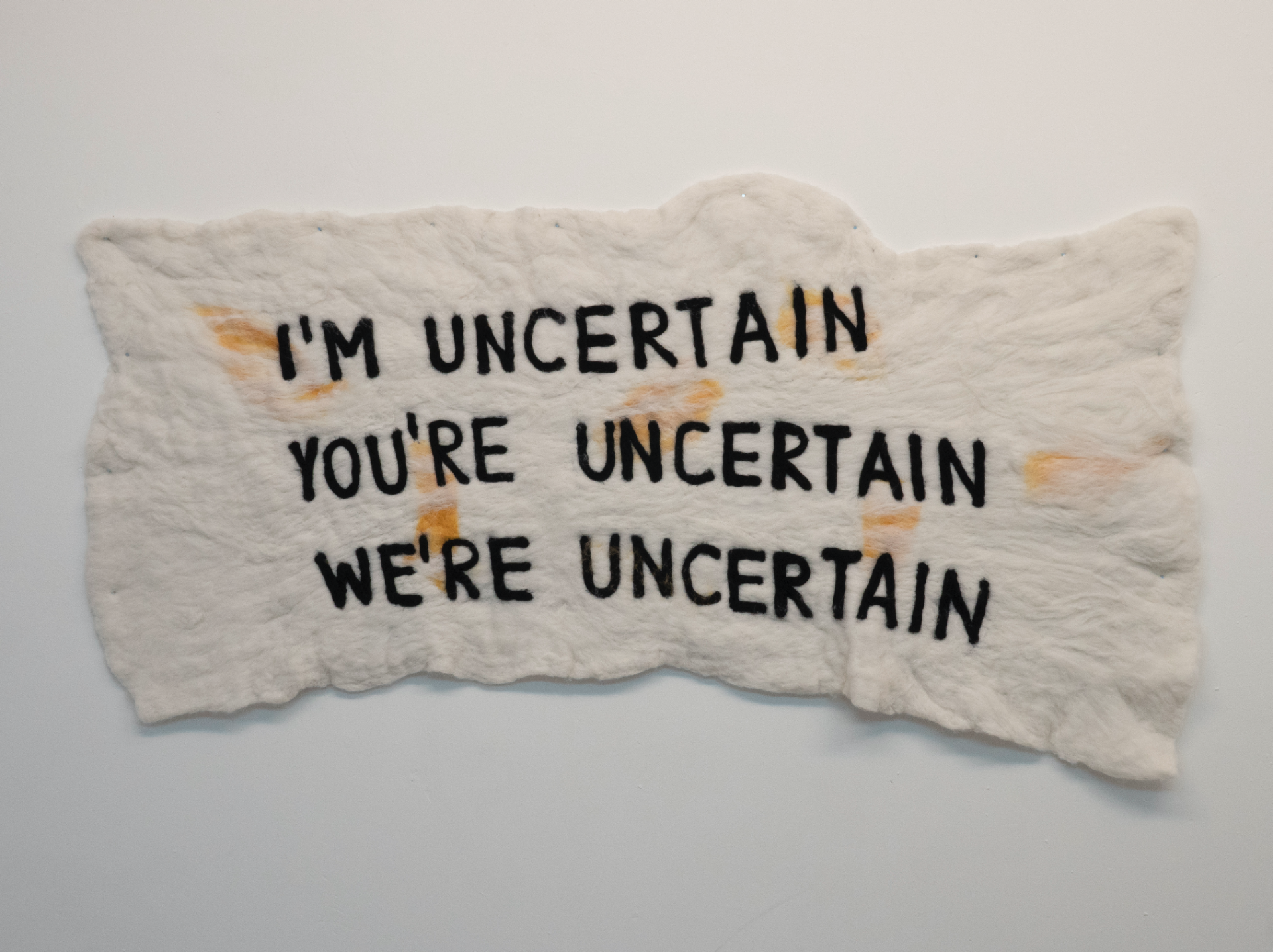

This led me to begin working with textiles – especially embroidery – and it made me feel like I was a part of a history that stitches its reality on cloth. While doing so, the hands have to take care and have to put things together. I couldn’t help but think of Penelope, weaving by day and unraveling by night, responding to her specific situation with resilience. Like her, others have waited actively by working with textiles. Because I missed the audience, I also approached the performance as a reflection on the emotional aspects connecting the performer and the audience. So the work is built around the more intimate aspects – the anxiety and excitement of seeing someone and needing and wanting to connect with them.

Larisa David, Come Closer, 2019, Rathaus für Neue Kunst, Lichtensteig, Switzerland, photo by Hanes Sturzenegger

Attila: Do you mean physical presence? We are experiencing online relationships more and more, so it’s expected that different forms of feedback will appear on the internet – not only someone’s attention, but also emotional aspects such as fear, happiness, and loneliness. If attention, recognition, information, and emotions appear on the internet, this can reshape our comfort zones. How do you think the need to connect is related to the loss of the world we knew? Is the fact that we are more and more emotional due to us undergoing a transformation?

Larisa: We are inherently social, and most of us are constantly looking for ways to feel connected to others – trying not to feel lonely. When we can’t physically be in the same space together, we try to look for emotional intimacy through our online presence and relationships. I guess I and probably my generation are well-versed in online relationships because most of us have had the experience of travelling or constantly moving. What I presume is perhaps happening at the moment is the increase in collective forms of being together online – exhibitions, talks, events, and so on. But I think at the same time we are more emotional because it’s hard not to be. It’s a time when precarity – a state that was already a constant companion to some – effects a great deal more of us. It’s also a moment when it’s hard to not feel anxious about the future. This creates more space in which to talk frankly about our emotions, rather than minimizing them or seeing them as personal failings. It might also bring some wider understanding to the experience of loneliness and isolation as a social issue.

Attila: Many of your performances, such as See Something Suspicious and Come Closer, are dedicated to or related to emotions and the body. Are you trying to point out many different aspects or dimensions of emotions, or are emotions simply constitutive elements of your performance because they mirror a reality that you capture? How do you choose your topics? Can you talk about your working methodology?

Larisa: Within my work, there has always been an interest in the body, and there are many intersections between my own experiences and my exploration of different perspectives. Since I moved to the Netherlands, I have started working with performance more. At the same time, I also became interested in collapsing fiction and reality by using autobiographical details at times, but I always kept to a disjointed and fragmented format by using varied sources. I usually write scripts in which I combine found materials and my own texts. After I moved to the Netherlands, my works attempted to explore the experience of simultaneously being an insider and an outsider and the ambivalence that it entails. I started wondering what gestures were used to mark a person as being or acting strange. This made me reflect on how it feels to physically inhabit and move through a world where one is seen as a stranger. Acts of appearing, recognition, surveying, denouncing, obscuring, and blending in became relevant in order to question who or what is seen and from where. See Something Suspicious, for example, is a performance that, by looking at movement in the public space, explores the interval between being suspicious of those around you and being under suspicion in an environment. With Come Closer, I was more interested in scenarios of coming together and moving forward. The performance teased multiple relationships by imagining those present successively as game or hunters, unwanted visitors or fickle guests, and spectators or seekers.

Larisa David, Waiting Tenses, 2020, Available & The Rat, Rotterdam, Netherlands, photo by Lili Huston-Herterich and Sophie Bates

Attila: You stated once that your works “seek to bring marginal histories to the stage and investigate modes of interfering, interrupting, and misbehaving.” Would you comment a bit on that – on the necessity of being engaged or approaching misbehavior?

Larisa: I find it interesting, for example, that something as mundane as a Sunday stroll through the park brings up thoughts of the history of middle-class walking practices in Europe – strolls were all about being seen and seeing others. Imagine, in that upright posture with limited movement, how a stumble could interrupt the performance. Such small movements have the power to interfere with social order. On the one hand, this shows how roles are scripted and what knowledge is required to perform them, and on the other hand, it makes them visible and possible to act against them. I tend to think that when we bring in intentionality, such as stumbling on purpose, failing to behave, being insolent, refusing to be productive, and so on, then it can open up new ways of navigating the world in order to oppose neoliberal structures as well as patriarchal and universal paradigms. Knowing that there are always ways of just saying “no” and that, to quote Anne Boyer, “History is full of people who just didn’t,” [1] keeps me sane most days.

Attila: Many say “no” in the form of collective protest, while others do it individually. Are you interested in social or political involvement as an artist? Can your actions, performances, and works be listened to or read by the general public, or by a specific audience, as a political message?

Larisa: My works are open to multiple readings, and there’s a definite political element to them, but I don’t particularly relate to them as a political message. My methodology is informed by intersectionality, affect theory, and phenomenology. I am interested in looking at how things come to be, and I think it’s important to trace their circulation through space and history. I am also interested in thinking of the space that I create within my works as a place in which there’s a circulation of movement and affect. Through this, I also aim to invite forms of solidarity and collectivity into my work.

The text is a part of an ongoing series which aims to introduce the ten artists who will participate in the upcoming festival of performance art We Are All Emotional. The event will take place in the autumn of 2021 in Prague.

[1] Anne Boyer, “No,” Poetry Foundation, published April 13, 2017, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/harriet/2017/04/no