Collaboration is a ceaseless negotiation between closeness and distance

Judit Angel in conversation with Anetta Mona Chișa and Lucia Tkáčová

Anetta Mona Chișa and Lucia Tkáčová, The Gut, 2020, public sculpture in Schillerplatz Chemnitz, part of the project Gegenwarten | Presences, Chemnitz, Germany, photo by the authors

Judit Angel: You have been working together as a duo for more than twenty years, and if we consider only the process, without the output, this is already a performance in itself. But your body of work is quite extensive, spreading across different genres with collages, photographs, tapestries, objects, sculptures, installations, videos, performances, and pieces that fit in between these categories. Since our interview is apropos the performance festival to be organized later this year in Prague, entitled We Are All Emotional, Have We Ever Been Otherwise?, I suggest viewing your art through the lens of performance/performativity. The strong presence of the (human) body comes immediately to the fore, be it your own bodies, the body in action, the staged body, the living sculpture, the body as obstacle or confrontation, fragments of the body, and more. Looking back on your practice, how would you describe the role and function of the body in your work?

Anetta Mona Chișa: You are right, the performative body was always present, not only as a subject or a medium, but also as a condition for our collaboration. Working together requires multiple rituals of metabolic syncing – from fine-tuning our time, space, feelings, and awareness to chemistry and sleeping patterns. So, on one hand, intercorporeality, as well as intersubjectivity, were always key; I would say that our bodies perform our collaboration in a perception-action loop between the two of us. On the other hand, the body is pivotal to our understanding and expression of our place in the universe; it is the place of multiple alliances, symbiotic connections, and fusions. It is the articulation of human existence, man’s relationship to nature, and complex social and political issues. So, the body was always at the core of our works, but the way we use it has changed over years. From being a vast plain for the expression of ideas relating to personal and public identities, sexuality, and gender to an attack on the very concept of identity and the discovery of the multitudes contained within (not only human) bodies. We are (active) in the world through our material presence, and the body is a strong ingredient in creating social horizons of hope and sustainable change.

Lucia Tkáčová: The body is everything: it is the material, the medium, the message – it is home. Human experience is always embodied. Through embodiment we are “worlded” – socially, politically, economically, culturally, historically – as well as directly immersed in the Here and the Now. The physical experience of being worlded fundamentally shapes our thoughts and actions. The basic concepts of our consciousness are articulated by the movement of our body in space – they divide reality along corporal axes and establish basic dichotomies. For instance, the physical antinomy up/down nurtures the notions of heaven and hell, instigates hierarchy, and permits class. It is an entirely human category, brought about by the upright position of the body. Beings that crawl or see with the entire surface of their bodies perceive up and down completely differently, if at all. Their social structures and notions of the afterlife must differ accordingly. Front/back establishes future and past as well as the toxic cogitations of progress and regress, while left/right divides the world ideologically. The dichotomy in/out, bears the “I” and the “other,” opens the gap between “me” and “the world,” births the distinction between individual and shared, creates “us” and “them.” In my opinion, of all these dichotomies, it is the most existential, most mysterious, and most related to collaboration.

It seems clear: layers of reality are nested in each other – a world in a universe, a body in a world, I in a body. There is a hitch at the end of this neatly ordered line – I in a body. With a jolt, we arrive at the limit of thoughtwords and on the boundary of an ineffable experience. What is a body, and what is I? Am I in a body, am I a body, or do I have a body? The field that unfolds with this twitch creates space for transmission, for collaboration, for art.

Judit: Another important element, especially in your earlier work, is language. There are various ways your works resort to the performativity of language. More direct examples include the series Dialectics of Subjection (2005–2006) and The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (2010), in which the spoken text aims at deconstructing stereotypes about women and norms imposed on them in male-dominated society. Before or After (2011) is a collage series based on photos of protesting women, where the use of the conjunction “or” puts the reader/viewer in a position of oscillation between alternatives, ultimately affirming incertitude as a form of protest. What is your experience with the power – but also the limitations – of language?

Anetta: I was always fascinated by language, by both its power to change and its ability to be a trap. Migrating through different languages in my life, I often experienced how language reveals and reflects power, maintains existing dominance, reduces and increases human misunderstanding, unites and divides, and shapes our semantic environment and our individual realities. The language–power connection is dynamically interrelated, one influencing the other. One symptomatic case of this relation that we are experiencing today is the sticky trend of cancel culture and the policing of language. It seems to me that this fashion has hijacked the struggle against oppression to perpetrate a divisive and destructive ideology of its own. Many words are newly suspect, whereas some terms are overused because they are “enlightened.” Tribalism decomposes useful notions and creates new categories of identity politics, linguistic safetyism, and bureaucratic norms. Shaming is used as an intimidating device to shut down social engagement or political expression. This hierarchization of vocabulary makes interaction more difficult. I believe language needs to be detoxified from its roots non-hierarchically, with intellectual humility, with creativity and imagination. If the limits of our language mean the limits of our worlds, as Wittgenstein would say, then we should invent and manage more sophisticated methods for expanding language and thought (rather than banning words and manufacturing culture wars that are being fought with and on words).

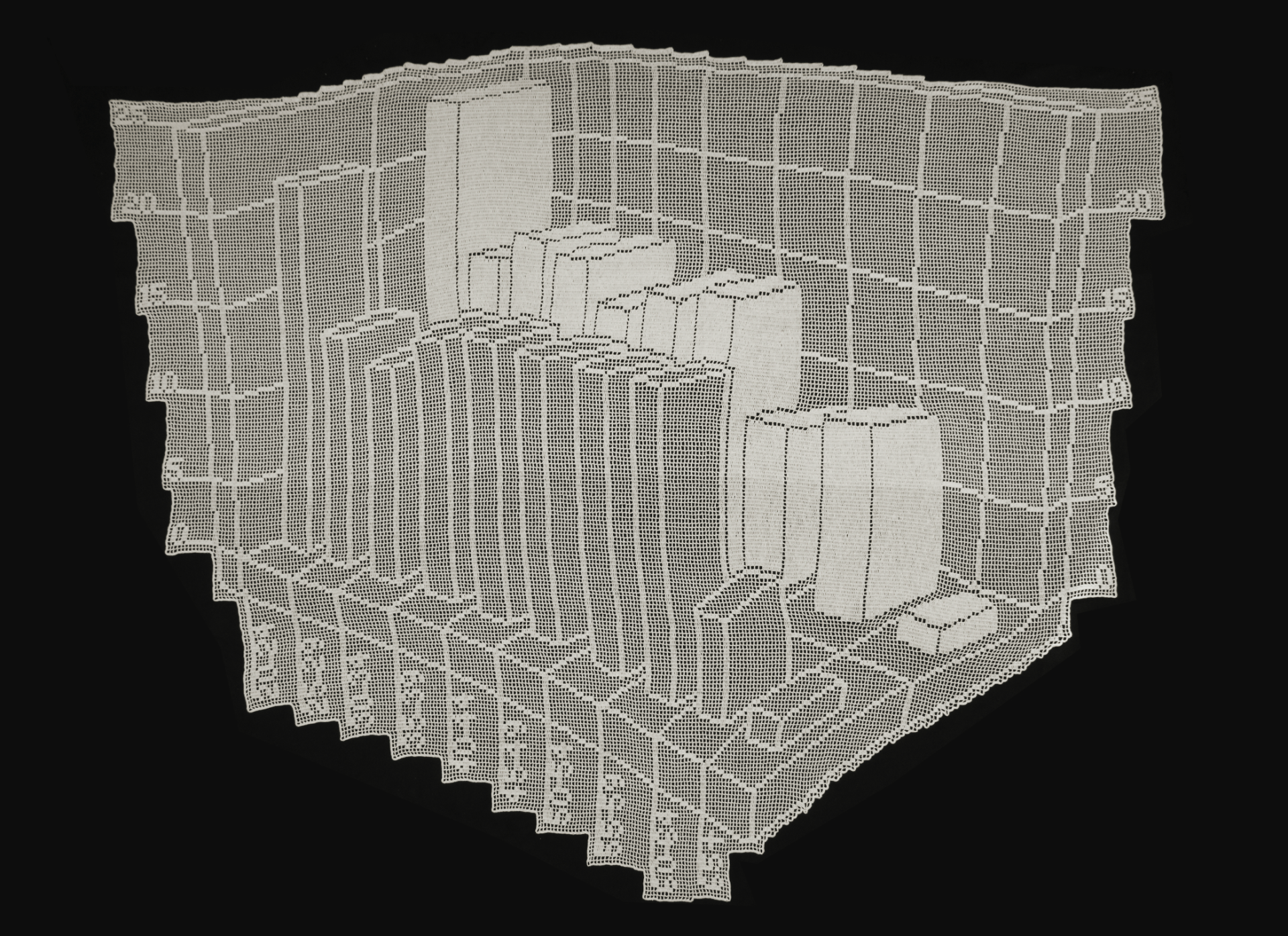

Anetta Mona Chișa and Lucia Tkáčová, When Labour Becomes Form, 2007, handmade crochet, 130x160 cm, cotton yarn, Courtesy of the Gallery of Modern Art in Hradec Králové, photo by the authors

Lucia: Our practice has been, foremost, a connection of minds. Preceding the invention of telepathy, such relation heavily depends on words and on the ability to articulate, to be understood, to become transparent. Being reliant on language as our main working tool, we have been simultaneously surfing its power and suffering from its constraints.

There is a lot of ambiguity, a lot of although-s and at the same time-s, in my relation to language, a lot of nevertheless-es. Language simplifies things into meanings. It breaks away from the smelly, warm, convoluted concreteness of a body and shields the mind from the overwhelming complexity of the world. Although inherently based in and producing distance, language can create intimacy and solidarity. This ambivalence makes it fitting for maintaining a collaboration, which itself is a ceaseless negotiation between closeness and distance. Meaning is born in a gap, in between: a word and a thing, two minds. It needs distance to exist – it fills it and at the same time creates it anew. Preoccupation with meaning seems to be a natural symptom of a collaboration, which also always happens midway, between.

In our practice, language became an agent for eugenics – it determined which artworks would be born and which would be aborted. Art has layers finer than language, which get burked< >bullied< >bulldozed in attempts at verbalization. Especially in the early, prenatal stages, when the leaves and roots are still fragile, articulation can be lethal. In this respect, whatever survives our creation process is resilient enough to withstand the translation into words and back. The ability to stand firm in language makes our works accessible and solid – it gives them power.

Collaborating in language can accelerate and sharpen things up, but it can also flatten and constrain them. We are like spiders, spinning threads of words between us, weaving a web of meanings, thick and elastic. At the same time, we are flies – the more we move in it, the more we get entangled. Thrusting through the thicket of language, we are looking for guides to show us a way out: plants, bones, pixels, fly agarics, weaving, matter.

Judit: While you have done only a few performances so far, many of your works have performative aspects. Some pieces are based on previous actions, such as Private Collection (2005–2010), wherein each element is added to the collection by a subversive action, or When Labour Becomes Form (2007), which is the result of a work – a performance. The iterations of Far from You. Memorials to Lída Clementisová come into being through instructions, while the potential of action is visibly present in Clash! (2012), even if there is no proper activity involved in the installation. Compared to your earlier works, your output from the last 5–6 years has been less processual and more object-based; nevertheless, these works are the result of certain liberating acts. How do you see this trajectory from process to object? What is your relationship to performance/performativity now?

Anetta: Performativity is implicit in the process of making anything, especially in an artistic collaboration. Collaborative art making is a complex and powerful verbal experience that presupposes a shared language, common goals, and the ability to negotiate across differences. It involves a specific methodological orientation and a reality-producing dimension. The original meaning of the notion of performativity refers to language’s ability to produce an effect beyond the realm of language. In other words, performativity means one can do things with words. I perceive both speech acts and symbolic, nonverbal communication as performative utterances. Although we never subscribed to one main medium, but rather roamed free in the world of artistic expression, the performative underlines all of our works, whether they are sculptures, videos, or scenarios to be enacted. Our working process combines (sometimes different) ambitions, tests desires, transmogrifies concepts, and dissects patience. While it is fun to do things together – it gives each of us a tingling dose of self-reflection, feedback, control, boosted objectivity, and mutual backup – it is not only about playing comfortably. It is more of a passionate interplay in which we often end up representing opposing positions. We nurture confrontations which allow radical visions and new ideas to sparkle. During all the years of working jointly, I have understood that creative collaboration and co-authorship imply many visible and invisible bargains, seeking uncompromising compromises, ego expansions and contractions, empathy and sympathy, opposition and relativity, tolerance and love. All of this is performance.

Lucia: Our tendency to “materialize” sprouts from many roots, the yearning to escape language being one of them. Although materiality is a condition of possibility for language, the power of language is substantial and substantializing. Still, matter has properties – physical, chemical, temporal, aesthetic – which exist and fully blossom in the outskirts or underground of language, even entirely outside of it.

I see matter as more autonomous than language, which makes working with it exciting. It is more of a collaborator than a tool. Materials bring something that we cannot fully influence or control into the creative process. The objects’ aesthetic grows out of their material nature, and we respect it, accept it, listen to it. The material decides, too.

There is always a process before/behind our objects; they result from a specific performative procedure – alchemic, meditative, psychedelic, digestive. Paradoxically, the performativity that precedes and determines the forms keeps them hostage to language. It becomes invisible in the outcome but remains crucial – it makes the work whole. Thus it needs to be retrieved and transmitted, described, ad-dressed in words. Language is not an inherent feature of performativity, but it can be its side effect.

Anetta Mona Chișa and Lucia Tkáčová, Private Collection, 2005–2010, installation in the exhibition The Making of Art, Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, Courtesy of Collection Collective, photo by Norbert Miguletz

Judit: Your artistic methodology comprises conceptual tools such as literalness, inversion, and complementarity, which are requisites of critical thinking and practice. While maintaining a critical standpoint, a part of your recent works focuses more on the relationality of things/beings, on the power of the senses, and on experience – on thus far suppressed/marginalized forms of knowledge. In your texts you refer to a world of post-literacy and post-visibility. It looks as if you have entered a post-critical stage, which still advocates the necessity of change, but in different ways. How does this relate to the critique of the Anthropocene? How do you see the role and potential of art in today’s multiple-crisis situation?

Anetta: First of all, it is difficult to think how art might have a direct, positive effect on today’s crisis, which encompasses such grand dimensions and involves so many different issues. The chances of art successfully promoting any fresh political principles or triggering a real change in society is close to zero. We associate the term “Anthropocene” with human-caused geological, environmental, and climatic degeneration. We are all worried and feel the same about it. Runaway climate change has become the main subject for activism and militancy today, and the vast majority of contemporary art seems to illustrate this hot issue. However, the majority of post-anthropocentric and ecological art is met by nothing more than a wall of furious agreement. Additionally, there are many other major anthropogenic risks to the natural world and civilization (including some that might be bigger than climate change) which are not so in vogue; therefore, we tend to think and worry about them less, and art reflects on them only marginally. If we take, for instance, nuclear proliferation, destructive biotechnology, artificially-manufactured viruses, potentially hostile artificial intelligence, or cyber-based disinformation, these are imminent dangers. All these threats and the failure to recognize and mitigate them should be understood as a crisis of sensibility. For this reason, art can play a decisive role therein by enriching and transforming our relationship to other people and cultures, to technology, to the environment, to all living beings, and to ourselves. Art is a device for imagination. Its role is to revisit the tools of representation and the symbols of resistance while proposing (aesthetic) immunities that refuse to be evacuated and puzzling speculations that refuse domestication. In this way art has the potential to birth other worlds, temporalities, and lives that do not necessarily correspond to the routines of critical reading but have the potential to change.

Lucia: I see the biggest force of art in its transformative potential, which can operate in two directions – inwards and outwards. Inwardly, art has the power to change its own maker. The creative process resembles the alchemic magnum opus – the process transmutes, transubstantiates, and refines the one who conducts it. Out of the one comes the two, out of the two comes the three, and from the third comes the one as the fourth. In this sense, art-making can be seen as inner activism – self-work and self-care that expands the depth and width of the artist’s mindbody, strengthens and sensitizes it. The circuit is palindromic: artist makes work, work makes artist.

The transmuting force of art can unfold outwards, too. An artwork can pluck its experiencer out of the mundane and cast them into the uncommon or sublime – a sudden shift between two dimensions of the same reality. Here, in the rupture, the dislocated mindbody experiences things which would otherwise and elsewhere be impossible. It can happen on many levels simultaneously: cognitive, physical, emotional, sensory, neural, cellular. Art has powerful tools at hand: colors, shapes, surfaces, sounds, emotions, meanings, laughter, awe, beauty. The destabilizing effect of beauty is especially effective, cracking calcified senses like eggshells and preparing the mindbody for transmission. In this situation-state-place lies the potential for metanoia, the “change of heart.” Pity that the state of somesthetic enchantment is so fleeting – the challenged mindbody has a tendency to quickly return to the comfortable safety of well-worn normality.

Judit: How have you experienced the challenges of the Covid times? What have you learned from them? How does this influence the new work you are going to present at the Prague Performance Festival?

Anetta: I appreciate how the Covid times have pulled us out of a collective hypnosis. The lockdowns and social withdrawal endowed many of us with time and increased sensitivity. Time has flowed differently, new topics have come to the fore, and in general the need for change has been confirmed. The need to produce less and more meaningfully, to use the potential of simple means, to reduce travel, to engage in educational activities in both directions, i.e., to educate oneself and to act as an educator as well as one can. I think the coronavirus times are partly a return to “normal” – by normal I mean a hyper-sensitivity and attention which we often lack. Freed from the dictates of hyperactive extroversion, I was finally able to focus more on existential issues, see the world (and myself in it) as one vulnerable whole, focus on what is here and now, and appreciate what I used to take for granted in art as well as in life. These realizations and confirmations will definitely affect both the prepared performance’s subject and its course.

Lucia: Even before the pandemic, I lived in a kind of a self-imposed quarantine, so my everyday life did not change much. I spend most of the time in my head, in imaginations, memories, and plans. The official lockdown took away the internal pressure to “do more” and eased the fear of missing out. My practice did not change – I am anyway very slow. I wallow in ideas and roll them around my head for months before I regurgitate them into reality. The disappearance of opportunities for outcomes allowed me even more time to masticate.

I hope that the changes on the planetary level which are now germinating will cross the point of no return. Until the virus came and set events into motion, the world was running business as usual – the elites were battling over resources and dominance, while the plebs occupied themselves by hassling with livelihoods and status products, ceaselessly glued to screens. Spellbound by kittens, porn, celebrities, sports, and news, we were, and still are, handing the mandate to decide over our embodied existences to algorithms and oligarchs. Globalization and virtuality conjugated us into one large, immaterial, subjugated body. The virus kidnapped this body and hard-landed with it into an individual, mortal dimension of oximeters, ventilators, and last words. The company of other bodies became a threat, but we still remember that it used to be a source of euphoria, strength, and security. The fear attached to our own bodies makes us aware of the mystery of being embodied. Ruminating annihilation, our attention gets amplified – a perfect moment to grab the Here and the Now and tweak it.