Empathy and Shame

Georg Schöllhammer in conversation with Doris Uhlich

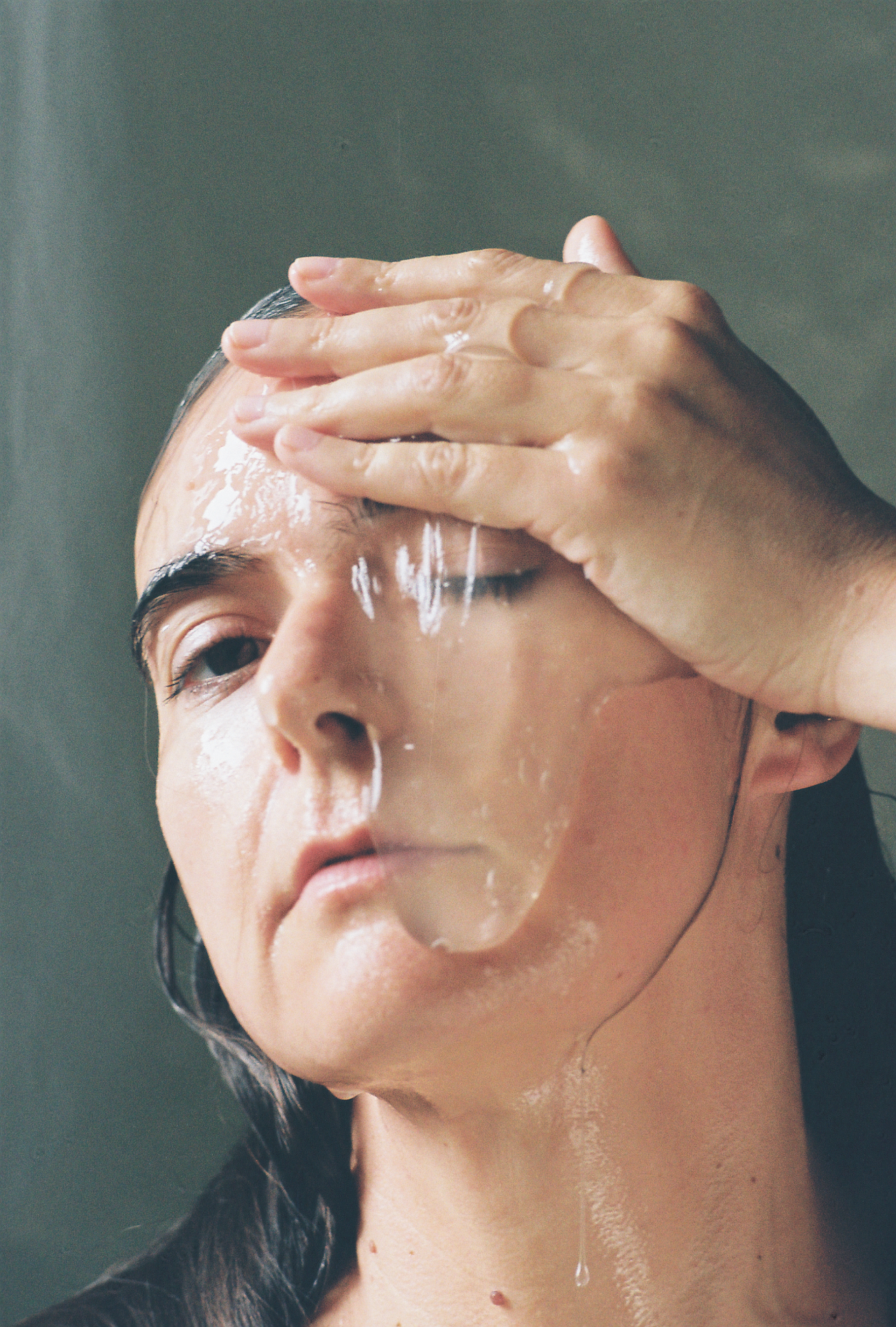

Doris Uhlich, Gootopia, 2021, Tanzquartier Wien, Vienna, Austria, photo by Juliette Collas

Doris Uhlich, Gootopia, 2021, Tanzquartier Wien, Vienna, Austria, photo by Katarina Šoškić

Georg Schöllhammer: Emotions and empathy are central motifs in your work, although here it is not a case of the blind empathy of compassion but instead a demanding stance that refuses to bow to conventions of seeing or of genre. And for you, empathy seems to be closely tied to solidarity and self-determination. How do you contextualize these terms in your work?

Doris Uhlich: The body is a complex storage system, an archive in which your own biography, as well as societal, political, social, and economic structures, is stored. Empathy begins in your own body and develops in relation to this complexity and the knowledge that the deposits there are not rigid structures. A body is a brain. Remix the brain. Mutual empathy comes from engaging with the other’s body archive and its history. In my work I try to show viewers how to confront what is inscribed in their own bodies, how to question their personal point of view and way of seeing things, and how to engage more deeply with them. As far as self-determination is concerned, people often perform in my projects who see dance an emancipatory tool for gaining visibility and transcending clichés. With respect to media, self-determination is about working to resist the force of media opinion-making.

Georg: Your choreographies and dance performances often deal with transcending various fixed social roles, including overstepping the bounds of what might be considered shameful.

You often work with nudity and deliberately go against commercialized body ideals. But I don’t think concepts such as “body positivity” are your main motive here. Nudity has in the meantime become a ritualized topos of the performance world. A strange notion of “essentialism” often seems to be behind such works, the ostensibly unbreakable unity of the body with the subjects and their gestures. Why is nudity important to you?

Doris: There are several areas of interest in this connection. On the one hand, I study movements that are only possible to do when naked and would not work with clothing, for example, my fat dance technique, in which I vibrate my flesh to make wave forms visible in the body. On the other hand, I am also interested in social nudity movements in the past and present, in how nudity functions as a body-political engine for change. I look for nudity beyond mere eroticism and ideologies, not naked poses but moving flesh. In some of my work, nudity has become a form of empowerment for people whose bodies do not conform to society’s ideal image. The skin is not an impermeable boundary but rather a permeable texture that raises exciting questions about what is inside and outside the body.

Doris Uhlich, Every Body Electric, 2018, Tanzquartier Wien, Vienna, Austria, photo by Alexi Pelekanos

Doris Uhlich, Habitat Halle E (pandemic version), 2020, Tanzquartier Wien, Vienna, Austria, photo by Alexi Pelekanos

Doris Uhlich, Habitat Halle E, 2019, Tanzquartier Wien, Vienna, Austria, photo by Theresa Rauter

Georg: Do you see your work as feminist and political?

Doris: I rarely use those terms in my writing, but feminist and political levels are intrinsic to my work. What is important to me as an artist is that my art may be, but does not have to be, political; art has no political mandate. Art needs the freedom to express itself politically and also non-politically (if that is even possible).

Georg: In one of your latest choreographies, you take a clear stand against the restrictions imposed by the pandemic and the displacement of presence into virtual spaces. The result is a piece that is at once dystopian and empathetic, in which the actors, dressed in virus-proof, transparent full-body suits, touch and embrace one another without being able to feel the others’ skin. How have you experienced the pandemic? What does it mean to you to be able to put on a physical event in a room with an audience?

Doris: Your impression that I opposed the pandemic restrictions is correct. I wanted touch, I wanted closeness. But it was also important to me to develop an artistic work that works with and not against the pandemic. Because of the pandemic, I came up with the idea of transparent full-body suits, virus-proof body extensions in which bodily evaporations and sweat were trapped inside and become visible.

Now that the pandemic has been going on for so long, I see it more and more as an impediment to artistic possibilities and shared experiences in which people are physically present in one place. I had to and still have to deal with regulations affecting rehearsals and especially the stage situation. For some time now, I have become more and more interested in the intermingling of performers and spectators in space – the kind of spatial constellation that is challenging to realize in times of a pandemic. A digital work functions so differently from an on-site event with an audience in a room. I am realizing that the screen is not suitable as an interface for many of my artistic works. You don’t smell sweaty bodies, your gaze is guided by the camera angle, and laptop speakers are poor at reproducing the actual sounds. Digitally, a button simply ends your presence when you no longer want to watch. In the shared real space there is no keyboard for clicking yourself away; instead, your body actually has to move to a different space. I find that more exciting, more challenging.

Doris Uhlich, Habitat Halle E, 2019, Tanzquartier Wien, Vienna, Austria, photo by Theresa Rauter

Doris Uhlich, Habitat, 2017, Wiener Secession / ImPulsTanz / Wien, Vienna, Austria, photo by Esel

Georg: It seems to me that collectivity is another feature of your practice. The collectives who perform on stage, many of them female, are heterogeneous in terms of both age and their level of professionalism as performers. Professional dancers are sometimes tempted to incorporate movement formulas from their own history and their past performances as set pieces, while amateurs sometimes orient their movements on stereotypes of supposed theatricality. Are you trying to break through these formulas? And what do mixed collectives mean for you?

Doris: The world has many bodies, and I find it vital to work with this diversity. I don’t feel that the difference between amateur and professional is so important as long as they all take a professional approach to their work. In the mixed ensembles, the focus is on the individuals with their own biographies and less on the trained or untrained performer. It’s all about mutual inspiration. At the beginning of a collaborative process, I address the possible “traps” – for example, that I am not looking for amateurs who take their cue from theatrical stereotypes and that I am inviting professionals to take part who don’t draw on quotes or past formulas but focus instead on the energy and materiality of the moment and the vision of their own bodies.

Georg: It appears to me that in many of your works there is an egalitarian moment as a way of blurring the boundaries between the private and public subject. Yet you create images of homogeneity out of this diversity. How do you choreograph that? Is it a utopia?

Doris: In my images of homogeneity, there is individuality. The starting point is a shared motivation for a shared performative moment. It is exciting to see how the same movement looks so different in different bodies with their respective dynamic possibilities. And yet the group is united by a common idea and vision. I like to create utopian spaces that can become a kind of short-term reality in a performative context. I’m thinking here mainly of utopias of community based on research into solidarity, empathy, and touch – between people but also in relation to unusual, alienating materials.

Georg: What, for you, is an ideal performance evening?

Doris: With that question, I already get hung up on the words “ideal” and “performance evening,” because I never use either term. I also work with durational performances and installation formats that take place during the day. And I would translate ideal as “successful in my opinion, alive.” I am satisfied when I notice during the performance how it manages to inscribe itself in the space, how time and duration take on a new dimension (at best, that time no longer matters), and how the experience continues to resonate in those present once the performance is over.

Doris Uhlich, TANK, 2019, tanzhaus nrw, Dusseldorf, Germany, photo by Katja Ilner