A Fair Artistic System Can Only Exist If There Is a Fair System for All.

By Dora García (commissioned by Verdensrommet)

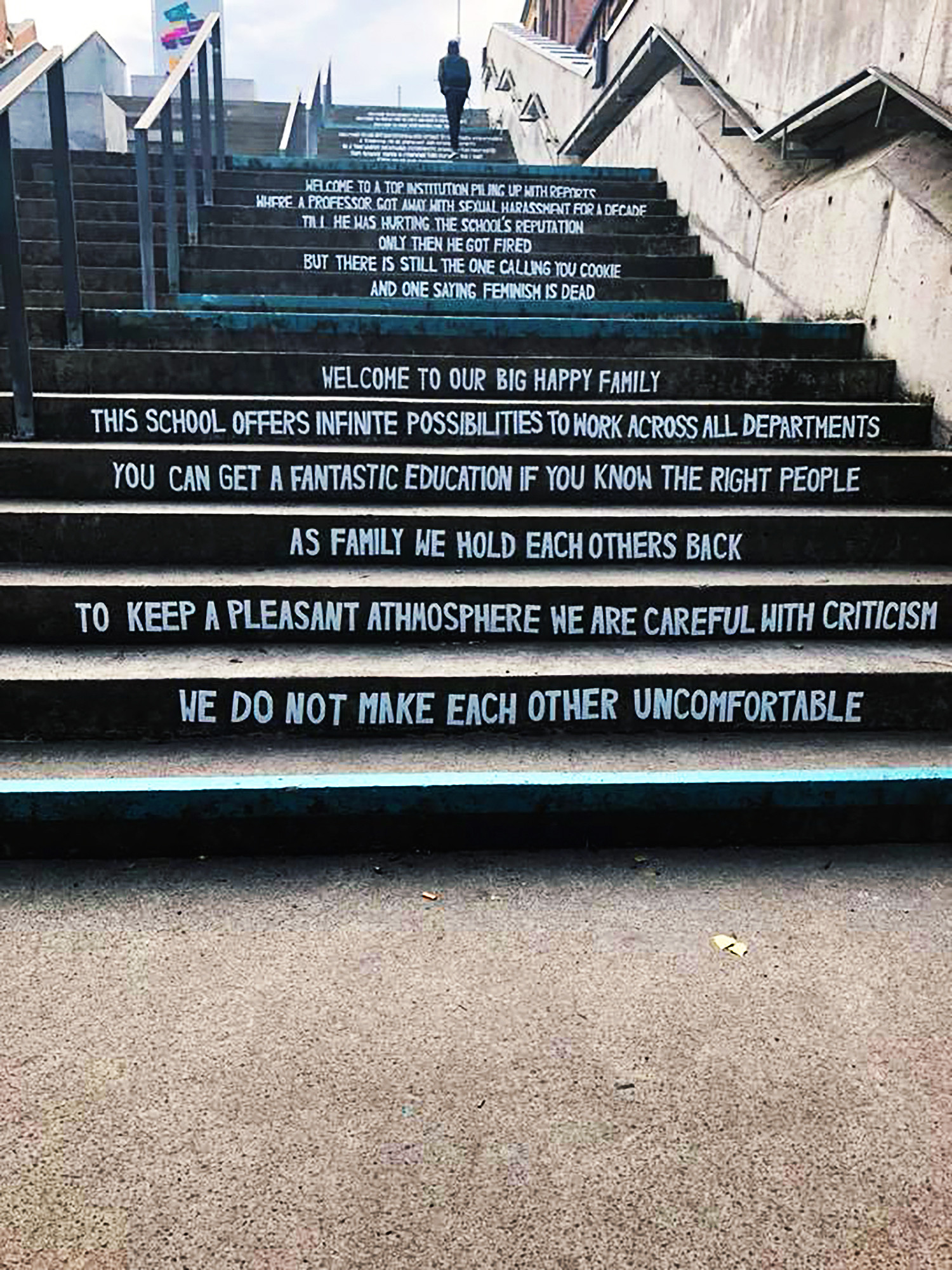

Stairs of the Oslo National Academy of the Arts, August 2018, photo Dora García

Stairs of the Oslo National Academy of the Arts, August 2018, photo Dora García

We advocate for unconditional universal basic income for artists and the creation of a mutual-aid and retirement fund to help manage economic uncertainty for artists in the present and the future.

The value of our labour is held in our creative process and collective knowledge, not in the production of measurable outcomes.

Artists don't have to accept the financial system as it is.

Jodi Rose, VERDENSROMMET CR8VX ARTISTS' SOLIDARITY ECONOMY WHITE PAPER

1. Places of Unwelcoming

I am an artist. I was born in Spain, and my native language is Spanish. I have spent all my adult life away from Spain—in the Netherlands, Belgium, and now Norway. This has been a voluntary exile from a somewhat privileged standpoint as Spain is part of the EU; however, when I first moved to the Netherlands to study, there was not yet free circulation of people within the EU—this came with the Maastricht Treaty in 1992. So as a student I spent the customary time in the immigration office.

In 1991, Spain was the periphery of Europe. Spain entered the European Union in 1986, together with Portugal, anxious for modernity and acceptance—Spanish and Portuguese artists were at that time completely exoticized, and I am sure that was the reason I was so quickly accepted to the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam, even though I was very young at that time and had no oeuvre at all. Soon thereafter, the fall of the Berlin Wall shifted the exoticism axis to the European East. I do not think that, in all the decades since, those exoticized peripheries have become centers, but rather the movement has been in the opposite direction—the centers have become peripheries. It is the same way that the colonial concept of the "Third World" turned out to be not an antechamber for the First World but rather a very specific model of global injustice that was and is ubiquitous in the so-called "First World." Third Worlds are everywhere.

In this sense, rather than using terms such as "peripheries," "Third World," or "Global South," I would rather use the term of "zones of exclusion"—"places of unwelcoming." The Unwelcome Ones are always the majority—the very concept of "holding privilege" implying a privileged minority.

My "vita" as an artist has been a learning process, obviously still in the making. This process could be best described as the progressive demolition of all preconceived until nothing was left. This progressive demolition encompasses all areas: artistic practice, artistic identity, art objecthood, social class, history, gender identity, feminism, economy, national identity, racialization, success, independence, failure, work, career, productivity, individuality, collectivity, sisterhood, colonial past, epistemology… the list is endless. This demolition brings me great satisfaction, and I understand the abandonment of ideas that were imprinted upon me by my education and upbringing as personal progress.

2. Nordic Character

The first time I set foot in Norway was to participate in the first edition of Bergen Assembly. One year later, in 2014, I applied for a professorship at KHiO (the Oslo National Academy of the Arts) and got the position. I was a commuter until 2021, and since then I have been a resident of Norway. The demolition of the preconceived ideas I had about Norway started early on, but the coup de grâce came at the beginning of the pandemic. That year, I saw how a very promising public art project, Oslo Biennale, collapsed for a multitude of reasons, but in my view the most significant one was institutional ineptitude. Also, after six years of considering my job at KHiO a blessing (I had taught before in Belgium, France, Spain, and Switzerland—so I could compare), I was suddenly able to see a different side of the educational institution—a very interesting side, but a bit of a disheartening one.

What was revealed following a discussion surrounding a large photograph by Italian artist Vanessa Beecroft is in fact a latent (or manifest) conflict that has been happening now for some years in many art education institutions: the art world is part of the world, and we need to take a position in it.

A group of students expressed their malaise regarding the exhibition of said photograph in the school common space; the photograph portrayed female models wearing blackface and afro hair wigs. Quite embarrassing, really—a relic from the nineties. To me, the situation was a no-brainer: the picture, having sufficiently outlived its epoch, had to go. But the discussion exploded, as often happens when one is sitting on top of a powder keg. Most students were vocal about the urgency of integrating post-colonial and gender theory into the art school curriculum. Others, a few, considered such theories—present in most European art school curriculums since the 2000s—to be an undesirable, foreign (US) influence, alien to the "Nordic character" of the school and also—try not to laugh—unnecessary as Norwegians are neither racists nor sexists. On top of that, those few also protested that they had enrolled in the school to be artists and did not want to be taught anything other than art—and art education should be politically neutral.

It is hard to analyze so many mistakes in a few sentences. Post-colonial and gender theory do not belong to the US; they are not alien. Foreign is not undesirable. I have no idea what "Nordic character" means, but I feel I am excluded from it. Norwegians are racists and sexists because everyone is—racism and sexism are something one must battle inside and outside oneself daily. What might be taught in art schools is the permanent negotiation (with the world) on what art might be and what it might be about. Everything is political. Nothing exists outside politics. Being neutral in politics means simply being on the side of the status quo.

Surprisingly, some Norwegian newspapers decided to give ample visibility to the reactionary students—and some reactionary teachers. It seemed that discussions within an art school were relevant for Norwegian public debate. The reaction found a surprising echo. And it resulted in the resignation of the school's rector. One of his reasons for resigning was that he might be "not neutral"—this astounded me. One cannot be neutral, shouldn't be. "Both sides" are not equal—one shamelessly exhibits its privilege; the other wants to end this privilege.

At that moment, I thought I should do something about this. I thought I could try to understand the connection between brazen privilege and art education—this meant a certain degree of institutional psychotherapy / institutional analysis (Guattari), as well as resuming the demolition of my preconceived ideas regarding art education as "the production of new artists." This production of new artists must examine its connections with capitalism, extractivism, self-exploitation, and the precariat. I am still there, in this process.

3. Open the Windows, Let a Fresh Breeze In

I met Rodrigo Ghattas-Pérez when he took part in the Master of Art and Public Space program at KHiO. I have since followed his work, and I have been very interested in the network initiative Verdensrommet, which he co-founded. I believe Verdensrommet touches upon some of the most relevant issues now at play in the Norwegian artistic community. I have read with enormous interest the "Verdensrommet CR8VX Artists' Solidarity Economy White Paper" put together by Jodi Rose. Their "Seven Keys for Creative Exchange in Artists' Solidarity Economies" echo many of the paths I am following when thinking about what a "fair" (non-discriminatory and just) art education institution should be like.

Some of those paths are, briefly stated: the equation art value = market value should be dismantled as it is false; it should be admitted, once and for all, that art practice is a precarious activity in capitalism, and it has always been, no matter how much they try to sell us the myth of the successful entrepreneurial genius—it does not exist; this precarity means that most artists do not have unemployment / sick leave benefits nor retirement pensions; artists should not be competitors to each other (they are not liberal professionals) but should, in good class-consciousness, be in solidarity with one another; the art system (we are all part of it) is sexist and racist, is exclusionary, because the world is—and it is full of "places of unwelcoming." This needs to be changed.

In August 2018, on the first day of school, my colleagues and I were surprised to read on the stairs of KHiO a very strong political message, which was the best (anonymous) artwork in the public space I have seen in a long time. The text read as follows:

Dear student / Welcome to one of Norway's crème de la crème elite schools / You may feel blessed, your dreams are coming true / Welcome to our big happy family / This school offers infinite possibilities to work across all departments / You can get a fantastic education if you know the right people / As family we hold each others [sic] back / To keep a pleasant athmosphere [sic] we are careful with criticism / We do not make each other uncomfortable / Welcome to a top institution piling up with reports / Where a professor got away with sexual harassment for a decade / Till he was hurting the school's reputation / Only then he got fired / But there is still the one calling you cookie / And one saying feminism is dead / Welcome to students and a faculty as white as the blinding walls / Where it is impossible for non-Scandinavian students to enroll / Welcome to a culture with no post-colonial and anti-racist perspectives / And a white smiling professor that uses the N-word to provoke / Welcome to the definition of a white cube / Welcome to an art institution reluctant to see power structures / A symptom of an ignorant and scared society / In a time where right-wing extremists dominate the discourse / This school should condemn this fucking bullshit / Step up to our expectations / Open the windows, let a fresh breeze in / Welcome to go against the existing structures / Welcome to break the silence and make it uncomfortable / Welcome to make your dreams come true / Welcome to love and fuck with KHiO / Happy to have you

I strongly believe that something radically changed the day this work appeared out of nowhere. We could not continue pretending there was no problem. In the many aftershocks of this brief institutional earthquake, there have been many back-and-forths, but one thing is clear: The artworld—and this includes the art schools and all artists' networks—is not separate from the world. A Fair Artistic System Can Only Exist If There Is a Fair System for All.

The text is a part of the tranzit.cz / Biennale Matter of Art project Center and Periphery: Cultural Deserts in Eastern Europe, funded by a grant from Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway (EEA and Norway Grants) in the program Culture.