I consider the ability to think, and thereby be cognizant, more important than the ability to empathize or sympathize

Dóra Hegyi in conversation with Hajnal Németh

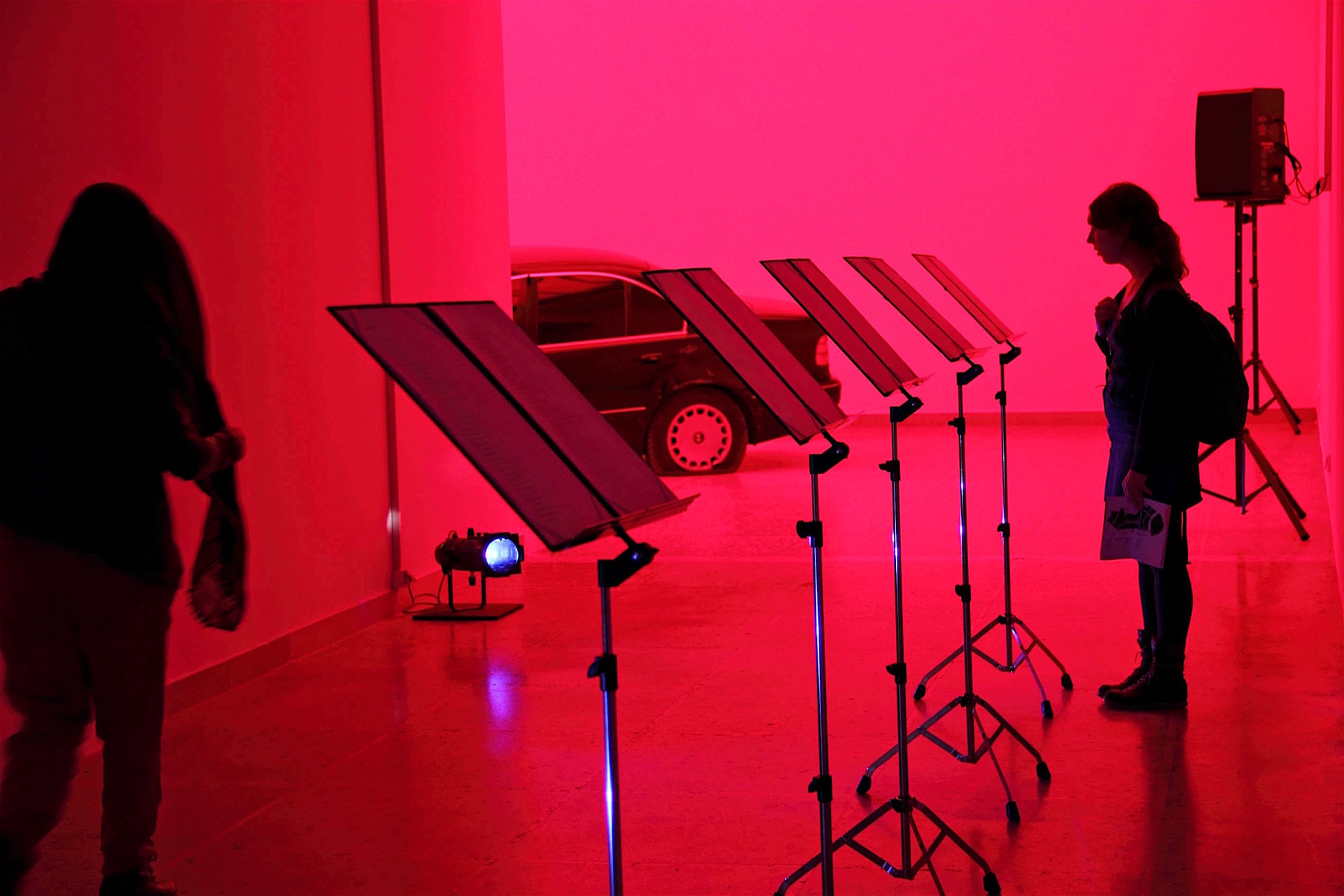

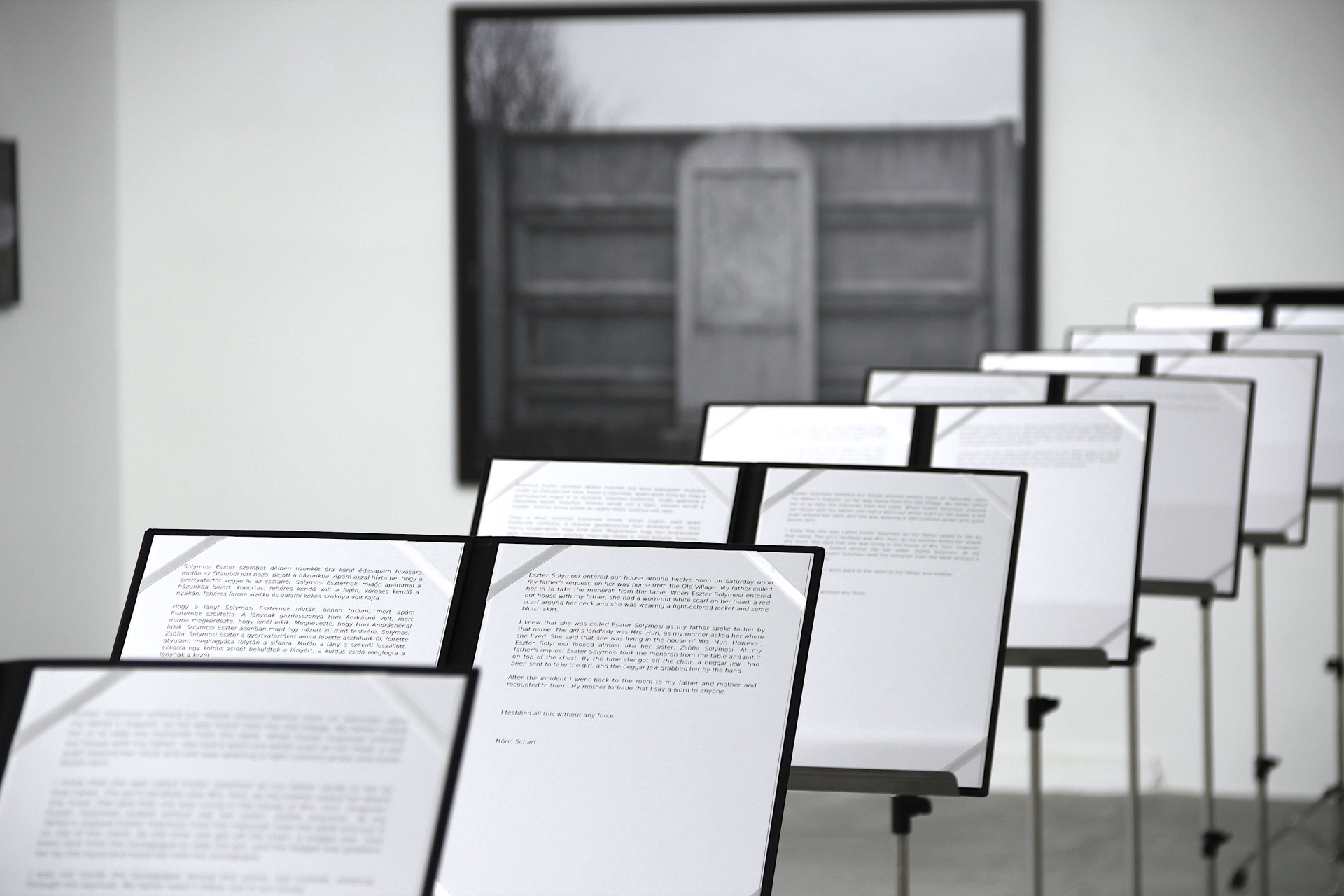

Hajnal Németh, Crash - Passive Interview, 2011, object and light installation with 8 channel audio, 12 librettos on music stands, 54th International Art Exhibition - la Biennale di Venezia, Hungarian Pavilion, photo by András Sólyom

Dóra Hegyi: Over the past decade, your works have been based on chanted music and text. What led you to this, and why do you choose to deliver the texts in your performances and films in song format? What is the role of having texts recited or set to music? What does performativity mean to you in general?

Hajnal Németh: My projects are predominantly process-based works that self-reflexively question the very process itself as well as its constraints in terms of form and genre. I regard the reinterpretation of the given genre’s framework as a point of departure from which we may move freely between forms without being bound by definitions.

The term performance is nowadays generally used to refer to performed works, but to me it stands for a show that is theatrical and representative in some respects and focuses on publicly carrying out a task. In this sense, my works are not so much performances as they are concerts through which I attempt to rethink the notion of the concert as a form, including a number of musical genres, such as opera, pop, rock, jazz, or musical.

To summarize, I intend to extend the notion of the concert as such and apply it to my process-based works, be they live events or recordings. All the more so because music is a fundamental element of my works, but not as a theme; rather, it is present as a component, as a device of abstraction. The content is in the lyrics, so my works are in fact almost exclusively text-based, and the theme is lifted by music from the level of narration and specificities to an abstract level that transcends itself.

Dóra: Your exhibition at the Hungarian Pavilion of the 2011 Venice Biennale featured Crash (Passive Interview) [1], a complex work in which an opera composed of dialogues about car crash experiences was presented in the form of a video installation. The texts that served as the libretto of the opera were chanted by singers at locations connected with cars: a car factory, a car repair shop, a car dealership, and the side of a highway. A crashed car was exhibited in the pavilion’s central space, and the dialogues were also put on display for visitors to read. The car crash, a dramatic, shocking event, was presented to spectators in a format reduced to minimalist text.

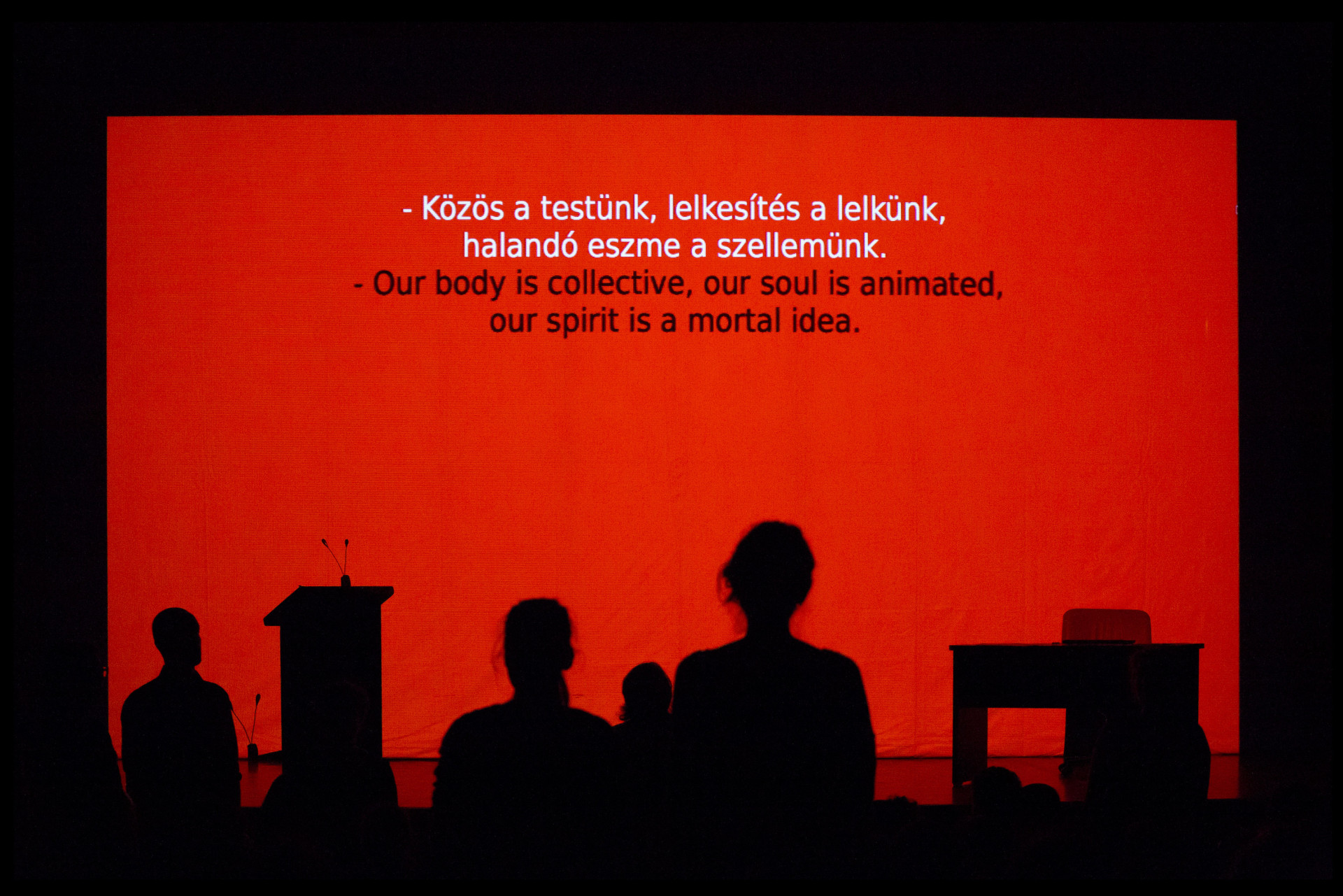

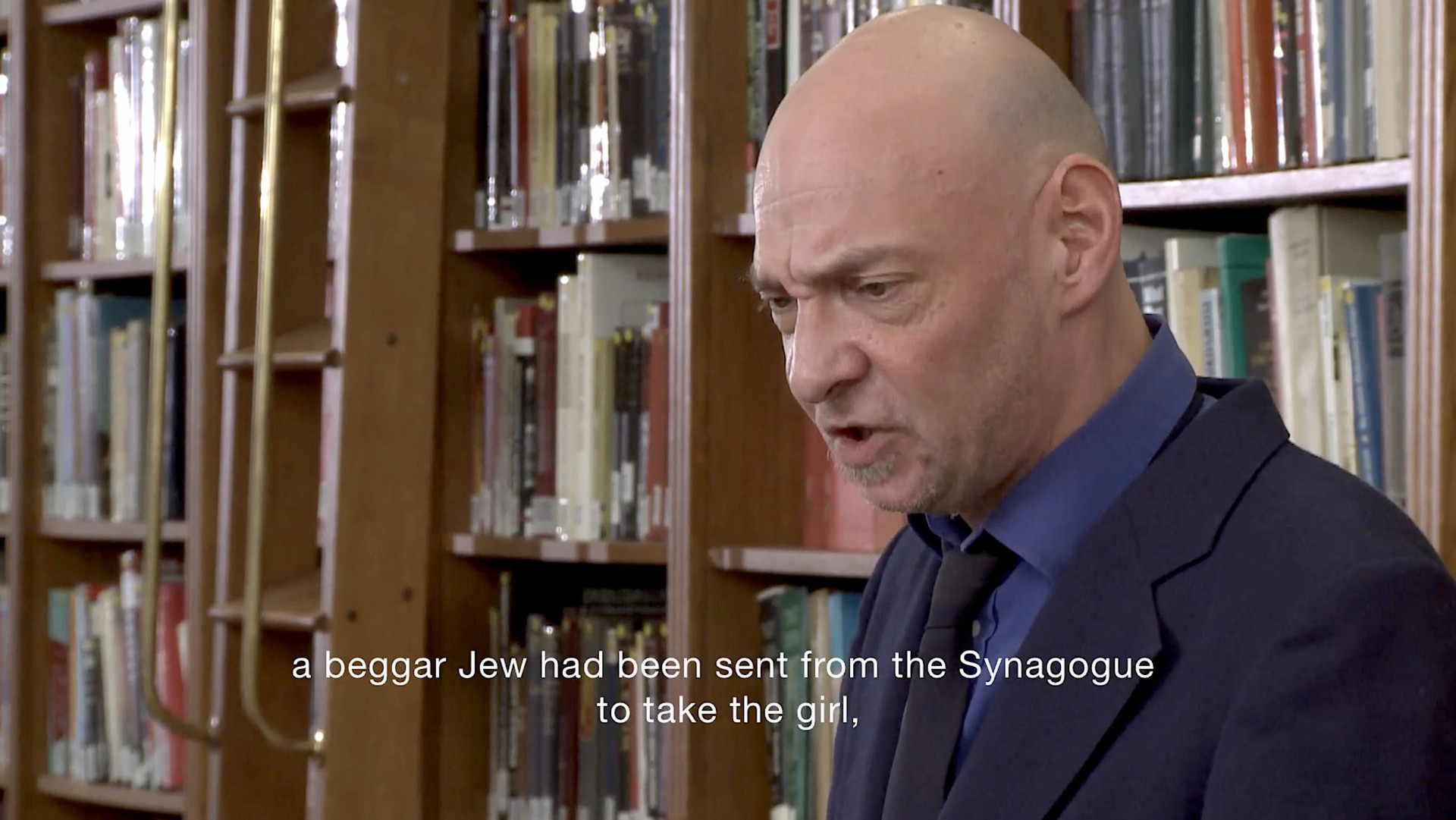

Another work from 2012, the choir performance entitled False Testimony (one Version of the Version) [2], was delivered live in a white gallery space and later in an office setting as the operatic film False Testimony [3]. For these works you used the screenplay of a film by Hungarian neo-avantgarde artist Miklós Erdély entitled Version [4], which was first produced in 1979. It was an experimental film that interpreted the story of a 19th century blood libel against a Hungarian Jewish community. Your work stripped this emotionally loaded story down to a minimalist opera.

Based on the works I have just outlined, what happens to emotions in the minimalist musical spaces that you create inside environments dissociated from the original stories?

And further, with regard to the theme of the planned performance festival organized by the tranzit network in Prague – We Are All Emotional, Have We Ever Been Otherwise? Towards New Gestures of Empathy – what role do emotions play in your artistic practice?

Hajnal: In progressing by way of abstraction from the concrete to a generally and timelessly valid meaning, emotions are also shown in a different light: instead of experiencing them, we comprehend them. In this context and in this manner, each concept and form serves to model and interpret the world, more specifically, the inner world, namely the “I”, and the outer world, the social political environment.

In Crash, the Passive Interviews model internal dialogues, and the answers given to yes / no questions are basically reduced to “yes,” which represents the unidirectionality and inevitability of the events that transpired. In these recollections of the moments of accidents, emotions are replaced by facts, just like in a police record. This is what the titles of the 12 librettos refer to: Record 1-12. The questions were actually adapted from statements quoted from accounts of people recalling their accidents.

Hajnal Németh, The Loser (The Citizen), 2015, experimental opera, 40', music by Dóra Halas, delivered by the choir Soharóza, Átrium Theater, Budapest, commissioned by OFF Biennale Budapest, photo by Boglárka Zellei

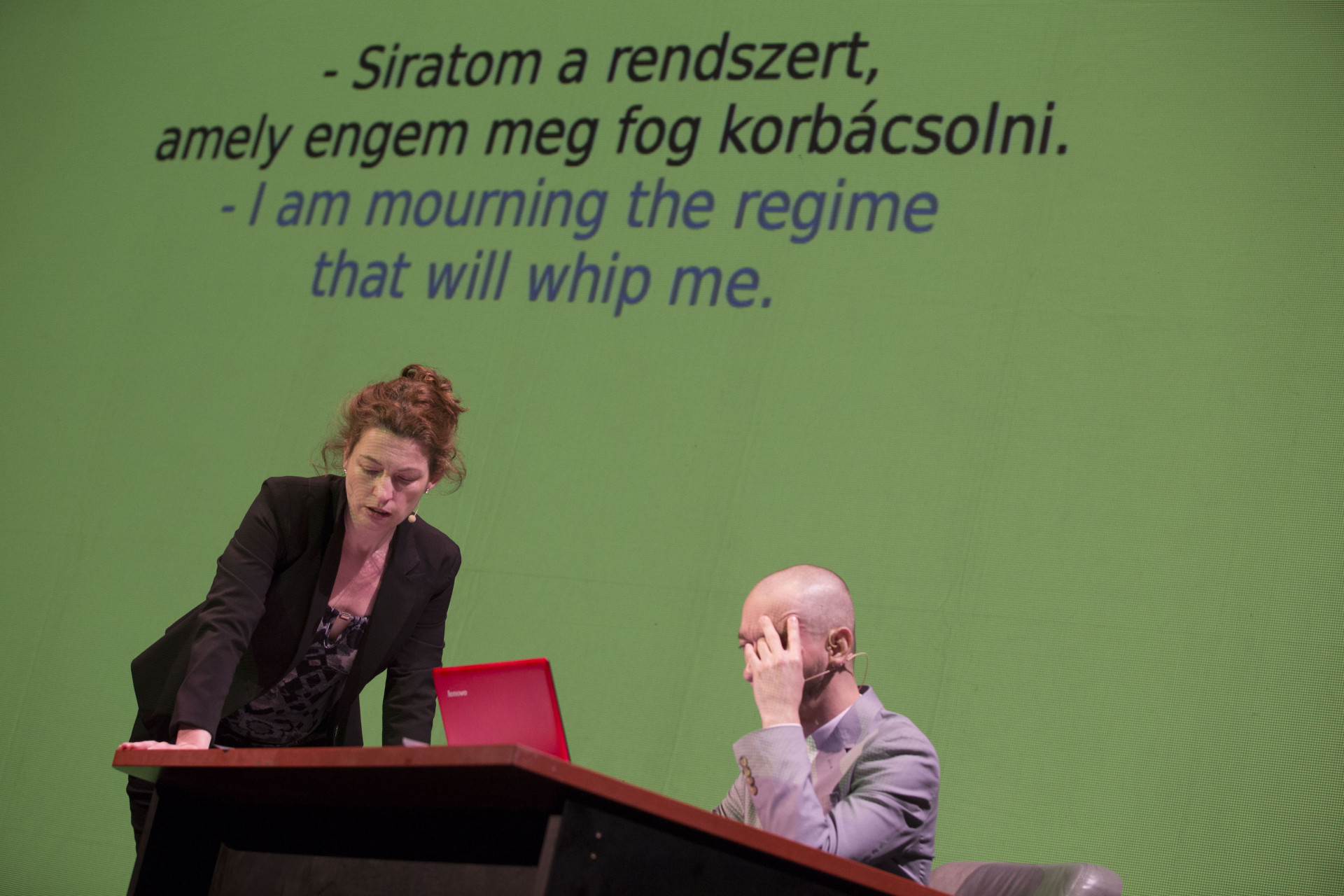

The dialogically-structured libretto of the opera performance The Loser (2012, 2013) [5] is also modeled on internal dialogues, namely the dispute between conscience and ego. We get an insight into the psyche of certain losers (the politician, the banker, the citizen, and the revolutionary) who accuse and absolve themselves. Their inner struggle eventually yields confession, which is more of an analytical conclusion than a bitter breakdown.

Hajnal Németh, False Testimony - Version 3, 2013, operatic short film, 17', HD, stereo, music by Dóra Halas, delivered by the choir Soharóza, commissioned by OSA - Open Society Archives, film-still by Béla Körtési

In the libretto of False Testimony, I quote the testimony of the principal witness in an anti-Semitic show trial of historical significance (The Tiszaeszlár Blood Libel, 1882-83) in 11 versions [6]. The first version is the original testimony in its entirety, and the rest are gradually reduced versions of the original. More and more facts and statements are removed from the text until only two words remain as a testimony: the undersigned name of the principal witness. In this work, both the libretto and its performance focus on the relationship between a lie and truth. While the performance represents the methodical recording of the lie, the libretto-installation models the methodical assertion of the truth by the simple deletion of the lie. The modeling of concepts and methods leaves no room for emotions, and the music of the performance is also more of a structural than a dramaturgical device, dividing the text into structural units and rhythm instead of filling it with emotions.

Hajnal Németh, White Song – Among Others, 2017, stage installation, textbooks and scores on music stands, acoustic guitar, guitar case, color projection, New Budapest Gallery, commissioned by Leopold Bloom Art Award, photo by Tamás G. Juhász

In the concert and installation White Song (2016, 2017) [7], the basic motif of hatred is put into words and song. However, instead of the refrain being targeted at groups of people, it is redirected toward various colors (white, black, yellow, red) thanks to the insertion of a single comma serving as a correction, for instance: “I hate the black, man.” This way the emotions are canceled out as it would be absurd to hate a color of paint with such extraordinary intensity. This work therefore highlights the absurdity of the emotion, which then translates into an applicable category in the case of hatred based on skin color as well.

Versions of Fear - Casting Nothing, my new work planned for the Prague performance event, is also going to analyze – but not express – one of the most fundamental human emotions: fear.

If an artwork intends to express emotion, it will have some effect. With regard to my work, I am interested in conveying thoughts instead of creating emotional impact. Or if emotions are involved, I am not interested in experiencing them but rather in understanding their mechanism.

Dóra: And how is empathy represented in your works?

Hajnal: Empathy is an ability that is indispensable for coexistence in everyday life and for the proper functioning of a community and society. Beyond sensibility, however, lies alertness – alert presence in a society, which requires intense and continuous attention and understanding as well as mentally active participation in social life. In order to understand others and processes, I must first understand myself and strive for self-identity. Lack of self-identity leads to an identity crisis, and in such a crisis, one becomes very impressionable and easily joins communities without understanding the motivations behind their cohesion or easily identifies with the ideologies of movements without being aware of their true meaning.

I consider the ability to think, and thereby be cognizant, more important than the ability to empathize or sympathize. It is from this perspective that my works address systems of relations, be it the relation between the individual and society, between two individuals, or one’s relation to oneself.

In terms of specific works that thematize these relationships, I would like to highlight three examples. The four chapters of the libretto of the aforementioned work The Loser and the opera based on it represent four social positions that give an account of their failure on an individual or social scale.

Hajnal Németh, The Loser (The Banker), 2015, experimental opera, 40', delivered by Andrea Csereklyei and Kornél Mikecz, Átrium Theater, Budapest, commissioned by OFF Biennale Budapest, photo by Zoltán Kerekes

The struggle and internal dialogue of the banker and the politician is modeled on an external dialogue split between two voices. One of them addresses the subject in the second person singular in a tone that is either confrontational or acknowledging, while the second voice responds in the first person singular, making excuses, denying, and eventually admitting. In this process of confession, we can merely observe the various emotions as the ironic language cancels out the drama. The confessions of the two other social characters, the revolutionary and the citizen, are rather introductions, in which each sentence is voiced twice, first as a solo song in the first person singular (“I am unsystematic”), then chanted by the choir in the third person singular (“He/She is unsystematic”). The way I see myself is therefore identical to the way others see me. We see the same, we state the same, so in this respect we are the same, and ultimately all of us are losers (“I lose, He/She loses, We lost”). The fall of society is caused by individual failures, and likewise, the fall of society also means the failure of the individual. Why everyone turns out a loser in the end is not important in this piece; it is no more than a hypothetical outcome. What is important is admission, or more precisely, the ability to admit. However, there is no empathy in the relationship between the solo and the choir. This relationship is more about a shared destiny, but the piece does not voice whether this shared undertaking is to be a conscious one.

Hajnal Németh, My Time, Your Time, 2020, karaoke stage installation, 2 textbooks on music stands, 2 microphones, color projection, Gallery ffrindiau, Budapest, photo by the artist

In my latest piece, My Time, Your Time [8], which debuted in Budapest in 2020, anyone can perform the two minimally yet fundamentally different sets of lyrics prepared on either side of a double-sided karaoke stage. In a similar format and with similar words, both sets of lyrics recount details of becoming homeless, the only difference being that one set is in the first person, and the other is in the second person. Is there a difference between “I’ve become homeless” and “You’ve become homeless”? Is this difference, if it exists really as minimal as the difference between the two poems? From what perspective do we assess the gravity of the problem: from the perspective of the subject or the object of the tragedy, from the perspective of the individual or society? This work is clearly also about empathy, most of all emphasizing its irrelevance if it only exists by itself without the ability to comprehend the tragedy and resolve the situation.

Lastly, I would mention the work Gravitation, Levitation (2015-20) [9], which comprises lyrics and scores for two child solos and two children’s choirs, presented thus far only as an installation, yet to be recorded. The piece is segmented into four parts – two prose sections and two songs. The first prose section features a child recounting the conversation of his parents preparing for a protest, and in the second prose part, the same child mediates a more sophisticated conversation. Accordingly, the first of the two songs strikes the tone of a march, and the second one uses a more liberated tone that rises beyond the philosophy of movements. Under what flag are we marching and where to? What ideology do we identify with and why? Does collective thinking exist, or is it merely the coordinated movement of people without thinking? Can we even speak of our thoughts in the first person plural?

In the form of poetic images, the libretto analyses the positions and stances arising in the relationship between the individual and the masses, revealing their inherent self-contradictions in ironic language. The segments that are meant to be read aloud take the ideology of the family as their point of departure and give way to broader, conflicting world views. The first part represents the acts of ideologies acquired without comprehension – which generate movements while being unmotivated – as a distorted self-portrait of the individual as reflected in the society. The second part represents the individual metaphysically identifying with himself in the form of a vision that transcends existence. The metaphysical approach speaks about neither emotions nor thoughts.

Dóra: In your performative installations you sometimes create situations into which the spectator can enter and become a character. In your latest installation in Budapest this meant taking the microphone and becoming a performer.

What is the significance of the different versions of your works? Sometimes you film a live performance, and other times different variations are created. What is your motivation in each of these cases?

Hajnal: Let me quote Laurie Anderson here: “This is the time. And this is the record of the time.” [10] To me, the fundamental difference between durational and process-based works is that in durational artworks (such as films, video installations, or sound installations), change takes place only within a given time frame, whereas in process-based works, there is continuous change – there is no precise and finite time frame. Durational works usually keep repeating a single sequence, while in process-based works it is an important formal element that the performance is live or broadcasted live, and even if a piece is performed more than once, it is never exactly the same.

Since I consider these two formats fundamentally different, I use different methods to develop a piece for recording than I do for live performance. The same libretto is used in both cases, but the location, the work process, and the performance itself are completely different. Most of my text-based musical works are therefore realized in two versions – one for recording and one for live performance. Live performances always adapt to the given circumstances, therefore a new version is born each time, which I usually mark in the documentation by numbering. However, the different versions represent more than formal differences. I am also interested in capturing the stages, so to speak, of the changes in content during the work process and in developing the version thus arising as an independent work. This method is another consequence of my “process-mania” – I regard the individual works not as concluded stories but rather as stages in a process ensuing from one another. I believe that the oeuvre is a process in which the individual works are versions of a single work of art. I am also interested in the concept of version as a theme. Many of my works expound on the notion of version or model the option of choice.

Hajnal Németh, False Testimony - Version 3, 2013, photo series and sheet music installation, 11 transcriptions, commissioned by OSA - Open Society Archives, Galerie Ebensperger Berlin, 2017, photo by the artist

As I mentioned, in False Testimony I developed, or more precisely edited, 11 versions of the principal witness’ testimony under the title Reduction, gradually shortening the original text of the testimony. In my projects Imagine War (2014-16), White Song (2017), and My Time, Your Time (2020), the concert or karaoke is based on modified versions of existing songs.

Hajnal Németh, Contrawork - Version 1 (Red Ford Mondeo), 2011, concert, 18 hours, delivered by István Dankó and Thomas Fischer, commissioned by MicaMoca Project, photo by the artist

The twelve acts of the opera Crash (2010-11) are basically twelve versions of car crashes. The three different librettos of Contrawork (2011-13) – Red Ford Mondeo, Dark Green Citroen and Blue Volkswagen Golf – comprise the story of dismantling cars of three different makes and thus present three versions of slow decay detailed by branding and technical specifications.

Hajnal Németh, Work Song – As Time Goes By, 2016, musical film, 55', HD, stereo, music by Brian Ledwidge Flynn, delivered by Gábor Altorjay, Desney Bailey, Knut Berger, Timothy Beutler, Polina Borissova, István Dankó, Lea Draeger, Júlia Koffler, Albert Orgon, Simon Fagan, and band, recorded at Studio P4, Berlin, commissioned by Berlin Senate, film still by István Imreh

The theme of the musical Work Song (2014-2016) is casting as such, namely the selection of actors for the roles in the musical, which is partly about introducing character versions: the passive voice, the directing voice, the obvious voice, the sceptic voice, the missing voice, the suitable voice, the selector voice, the resigned voice, the late voice, the present voice, the invisible voice, another voice, the free voice, and the controlled volume.

A further implication of my “process-mania,” is that the formal public representations of my works actually render the work process and my work methods transparent. My installations convert scores, music stands, instruments, and sound and lighting equipment into diverse stages, rendering them accessible to and usable by the spectators. The films made of the concerts and performances often document the recording process. Sometimes the venue is a recording studio, and the performers often read the librettos from their hands or from music stands. The accompanying photo series are often behind-the-scenes photos, and the posters, in a way, are advertisements for the shows.

I almost always take texts as my point of departure – I write, cite, rewrite, or redact, and the lyrics or librettos thus compiled are then performed and recorded. In some pieces I work with composers on specific sections, and at other times the music is spontaneously composed by the performers themselves improvising on the fly. I often annotate the texts with instructions, but I only partly define goals and tendencies in terms of the manner and style of the performance because it is important for the work to truly be created in the course of coming to be, and to that end the performers need to have enough legroom. The most radical example of this is the karaoke installation My Time, Your Time, in which anyone can step up to the microphone and perform the lyrics offered on the music stand.

Dóra: In recent years, your works have often involved the rewriting of existing lyrics. These revisions range from minuscule interventions, such as changing a word or two, to replacing entire lines. However, the important thing is that in every case the meaning of the text radically changes.

Why do you tamper with the poetry of music lyrics? What does this device serve in your practice?

What does the transformation of the signification of texts mean to you? Your aim is not to rewrite texts in a politically correct manner – rather you achieve a major change of meaning with minor transformations.

Hajnal Németh, Imagine War - Solo Version, 2014, concert, 30', delivered by Isidro Aublin, Galerie Ebensperger Berlin, photo by János Fodor

Hajnal: The lyrics that serve as the foundation of my works are generally based on my own writing, but occasionally I work with quotations. However, when citing lyrics, poems, or pieces of prose by other authors, I query the very gesture of quotation as a method. I do this by rewriting the cited text and developing a quasi-corrected but by all means arbitrarily modified version. The changes are sometimes minimal but still radical in the sense that they endow the text with an entirely new meaning, for example: Imagine War, Here Comes the Gun, and I Hate the White, Man!

By “correcting” the quoted texts, my aim is neither to transform the message according to some expectation, nor to make a statement that I deem correct. My goal is not to make a stand for or against something – I intend to model and reveal the mechanism of taking a stand and show that specific words or statements are definitive.

Some of the tendencies I follow when editing these revised model texts include updated recontextualization, mirroring, and cancelation of meaning. It is irrelevant to me whether the end result is politically correct or incorrect because the extent of political correctness is relative and ever-changing, depending on the time and place. It is this very shifting of signification that I intend to demonstrate by administering modifications. My versions are mere examples. Anyone can create their own version with which they can identify, if only for the time being.

Dóra: What is to be done now? Our lives have been constricted for more than half a year on account of the spread of Covid-19. This strongly affects performance arts, among others. What solutions are there for this situation? What are its implications regarding your art practice?

Can time-based artworks be planned online? Seeing as the performances you direct are often published in film format, could it be a solution for you to realize performances on film?

Hajnal: I believe we are living in an age when we have to exist with the constant sense of being in a transitional period. This began long before the coronavirus, but it was obviously the pandemic that made us aware of the current state of our existence. Our existential insecurity, the weakness of our systems, and the deficiencies of our vision for the future have become evident. We are unable to plan for the long term, and we need to be constantly prepared and adapt rapidly to changing conditions.

I have lived like this almost my entire life, as have most artists, I suspect.

I am aware of the crisis and will adapt to its forthcoming stages. I have never felt that I would be bound by the formal solutions I employed at any given stage in my career, and I consider it a challenge if I have to change my work methods on account of the circumstances. To me, work is about being in constant and active dialogue with the world.

The text is a part of an ongoing series which aims to introduce the ten artists who will participate in the upcoming festival of performance art We Are All Emotional. The event will take place in May 2022 in Prague.

[1] Hajnal Németh, Crash (Passive Interview), 2011, operatic film/8-channel audio installation/object installation, la Biennale di Venezia - Hungarian Pavilion, Venice, http://www.crash-passiveinterview.c3.hu/links.html

[2] Hajnal Németh, False Testimony (one Version of the Version), 2012, choral performance, 20 minutes, nGbK, Berlin, https://www.hajnalnemeth.com/index--works-2012-false-testimony-1-.html

[3] Hajnal Németh, False Testimony, 2012, operatic short film/photo series/objects, Invaliden1 Galerie, Berlin, https://www.hajnalnemeth.com/index--works-2012-false-testimony-2-.html

[4] Miklós Erdély, dir. Verzió [Version]. 1981; Budapest: Béla Balázs Studio. http://bbsarchiv.hu/en/movie/version-510

[5] Hajnal Németh, The Loser, 2012, operatic performance, 40 minutes, CHB - Balassi Institut, Berlin, https://www.hajnalnemeth.com/index--works-2012-the-loser-.html

[6] The libretto is based on the documentary novel by Károly Eötvös published in 1904: A nagy per, mely ezer éve folyik s még sincs vége [The Great Trial That Has Been Going on for a Thousand Years and Is Still Not Over

[7] Hajnal Németh, White Song, 2016, object installation/photo panel, Galerie Ebensperger, Berlin, https://www.hajnalnemeth.com/index--works-2016-white-song-1-.html

[8] Hajnal Németh, My Time, Your Time, 2020, installation - two-sided karaoke stage, galeri ffrindiau, Budapest, https://www.hajnalnemeth.com/index--works-2020-mytime-.html

[9] Hajnal Németh, Gravitation, Levitation, 2015 - 2020, installation - sound studio citation: acoustic screen, two song books for two child solos and two children’s choirs, two music stands, variable dimensions.

[10] Laurie Anderson. “From the Air.” Track 1 on Big Science. Warner Records, 1982.