Small acts of difference generate solidarity

Dóra Hegyi in conversation with Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara

Dóra Hegyi: In January 2018, together with art historian Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, you presented the performance Testimony of Fidel [1] at the Hors Pistes Festival at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, focusing on the theme “The Nation and Its Fictions.” [2] The audio piece, read out in a voice imitating Fidel Castro’s, expresses a kind of wishful thinking on the part of critical minds in Cuba. Castro is heard apologizing for all the mistakes he made to both the people and the economy. What was your motivation to realize this piece?

Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara: This piece’s basic motivation comes from the desire to restore the nation. Cuba is a very fragmented country – people are living in extremes. Some Cuban people, both inside and outside of Cuba, hate the communist regime, and some others, mostly representatives of this regime, hate those who don’t support it. If Fidel, before dying, had given his power back to the people, we would be somewhere else today. The work is basically an imagined testament which formulates the need felt by many Cubans for an apology from the regime. Just a simple apology and acknowledgement by the regime that they did wrong would do a great deal for many Cubans and could have meant a new start. Take, for example, Pablo Milanés, a famous musician living in Spain today who was in jail in the 1960s and for decades thereafter remained a public cultural figure and a believer in the revolution – today he demands the government offer a public apology for his imprisonment.

Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, Por un socialismo próspero y sustentable [For a prosperous and sustainable socialism], 2013, action during May 1st parade, papier-mâché puppets of Fidel Castro and Hugo Chavez, photo © artist’s archive

Dóra: Since the beginning of your artistic career, performance has played an important part in your work. You realize performances in the public space, and your statements have taken a more and more critical position against the regime in recent years. Your work often includes a sculptural element or object, which you, as a performer, activate.

Luis Manuel: Firstly, I come from sculpting. When I was a kid, I always preferred to make objects as they were much more real than drawings. A sculpture is like a living object in 3D, whereas a drawing is just a representation. When I grew up, I found a living space inside art. At the same time, I have taken into account that for me – a person who did not find much culture at home, has no proper education, and is black – it would be difficult to enter the established art scene. Realizing this, I started placing my sculptures in the public space so as to have them acknowledged. Gesture plays an important part in my work. I’m interested in works that “enter society” and by doing so stop existing as artworks. So, the people on the streets who see my “gestures” and my works don’t interpret them as art. Based on their pre-existing knowledge, they only see me as a human being, a Cuban, who is interested in commenting on social questions. So at these public appearances, like La Caridad Nos Une (Charity Unites Us) from 2013 for instance, they would just see a young Cuban, who they might think is a bit crazy, sacrificing himself by pushing a papier mâché sculpture of the Virgin of Charity almost 1000 kilometers as a private crusade. This happened parallel to the church-organized pilgrimage, which was connected to the 400-year anniversary of the saint. My act was a commentary on the visit of Pope Benedict XVI, on the hypocritical political regime, which had prohibited the practice of religion just 20 years before. This is how I understand that sacrifice can be an aesthetic space. Even politics or ethics can be regarded as aesthetic spaces. They are abstract but at the same time vivid spaces inside society.

Dóra: You also mentioned that you visited Tania Bruguera’s Cátedra Arte de Conducta (Behavior Art School) [3] in the 2000s and that the approach of taking a political stance and making an impact with your art also goes back to your experiences in this informal school community. How do you connect your work to what Tania calls arte de conducta (behavior art)?

Luis Manuel: Of course, Tania Bruguera was a big influence in my search for the spaces of action, an art approach that affects concrete reality. Cátedra Arte de Conducta is the most important educational format in the last 40 years in Cuba. Tania introduced new expressions and visions to my generation. The discussions there created a completely new space in our heads. They raised questions which we are not able to answer to this day, but we learned to reflect and act.

Artists protesting Decree 349 in front of the National Capitol Building, Havana, 2018, photo © artist’s archive

Dóra: In your work, you repeatedly reflect on the long-lasting, problematic relations between the USA and Cuba. In 2012, you created the work Regalo de Cuba a EE.UU. (A present from Cuba to the USA), placing a Statue of Liberty made of waste materials on the Malecón, the esplanade in Havana, on the 236th U.S. Independence Day. You also wrote a letter to the Office of Interests of the United States in Cuba informing them of “a present from the Cuban people to the people of the United States.” They did not accept the gift, and since then you have repeatedly tried to convince them to take it.

In 2015, when diplomatic and economic rapprochement between the two countries began, you reflected on the controversial consequences of these changes on the art world. You used the visibility of the 11th edition of the Havana Biennial, appearing in public as Miss Bienal de Habana (Miss Havana Biennial). Dressed like a female Cuban parade dancer, you handed out your business card with details of your real artist’s name and contact information, an action which received a large amount of attention. With this gesture, you pointed to the complicated situation of Cuban artists who become part of the “carnival” of the international art world in order to get attention; though in reality, they stand alone, lacking the support of local institutions for their careers as professional artists.

Luis Manuel: As I said, I’m a black person, coming from a marginalized neighborhood. My experience with politics, the economy, and the system is defined by a basic approach to life. I come from a part of society that doesn’t think about much other than the necessities of food, clothing, partying, and the need to try to find a future, inside or outside of Cuba. This is the reality that I was brought up in, which is also heavily intertwined with religion.

As a Cuban, from the day you are born, the USA is a constant reality from which you can never separate yourself but also never really know much about. Can the USA be that bad if all the good things come from there? So you live with this ambiguity. Your experience as a child is that good candy, good clothes, good films, good products all come from the USA. For instance, if you buy a branded shirt with the American flag on it, it costs more than a Cuban one. And it goes on throughout your childhood and as you grow up.

The piece you mention, about the Statue of Liberty, is defined by the desire for Cuban-American relations to get sorted out. This enemy doesn’t really exist. Since I was a kid, we’ve heard a lot from the UN that many countries are against the embargo, so we were really hoping that its suspension would happen. When things were finally fixed between the two countries in 2014–15, it was the happiest moment for many Cubans. When it was announced, people went out to the streets celebrating and saying that now we can leave this system and move forward. So, the relationship with the States is very extensive. It has brought hopes and frustrations and of course a lot of manipulation too on the part of the totalitarian regime. The Statue of Liberty made of old wood and clothes is a visionary project which talks about the necessity of reconciliation between the two countries. It also shows how, from scarcity and misery, we can still make a gesture so we can be friends. This is what I can offer you as a token of my friendship.

The other work, Miss Bienal, is about how Cubans used to prepare for the arrival of the North American cruises, which brought all the goodies from there, so Cubans couldn’t think of anything but McDonalds, Coca-Cola, and money. Nobody asked us how we would feel if all these big companies were to enter the country or how we would export our products. Also, many artistic institutions are focused on selling art [4] but not on actually making the viewer think much.

Actually, with my artworks, I intend to raise investigatory questions so people can respond for themselves or ask more.

Dóra: Despite the changes in the international political position of Cuba with the death of Fidel Castro and its opening towards the USA and other countries, the regime still feeds propaganda to the populace. This is obviously mirrored in the country’s cultural administration and cultural policies, which have become more restrictive over the last fifteen years as critical voices from a growing number of cultural actors were heard. [5]

A good example of these debates is the Havana Biennial, organized since 1983. It became an important platform for bringing together artists from Latin and South America and the rest of the world. [6] For Cuban contemporary artists, the Biennial is an important reference point. It brings current contemporary art and its discourses close, and it is undoubtedly an important site of visibility, which artists want to make use of. On the other hand, it also highlights the controversies of the Cuban political system, in that the event is not organized by selected or invited curators or artists but by people who are well connected to the government.

In 2018, the Ministry of Culture introduced Decree 349, which restricts artistic practice to those registered as state-authorized artists. This new law upset the progressive art scene, and you and Amaury Pacheco gathered a group of artists under the name the San Isidro Movement (named after the neighborhood where it was formed) to resist this authoritarian decision. With art historian Yanelys Nuñez Leyva you initiated the Museo de la Disidencia en Cuba, [7] a website that collects recent and historical resistance movements and the activities of freedom fighters which you contemporary dissidents can connect with, for example by liberating José Martí [8] from his position of an overlooked bust present in all schools and public institutions and seeing his fights for freedom as they happened. In 2018, when the Havana Biennial was postponed to the next year (ostensibly because of hurricane Catherine), you and your peers initiated an event in the independent art scene, the #00Bienal de La Habana, to replace the official event.

What was the relevance and effect of joining forces? How did the community and resistance movement grow?

Luis Manuel: It is important to say that I am a person who loves the institution. I’m not against it. I’m in favor of a plural and inclusive institution in which I can see myself reflected. The totalitarian regime wants the opposite; it wants to kill the way institutions function, to construct a totalitarian and centralized space through dictatorship.

I understand the Havana Biennial as a commercial act – of course very cultural, but predominantly commercial – with the aim of finding a curator or a collector. It lost the sharpness it represented in the 1980s and 1990s. Since 2015, the editions of the Biennial have been losing their seriousness, their investigative nature, and their cultural purpose. Lately, all editions have been focused on inviting artist superstars, so it has kind of lost its real purpose, and we created the #00Bienal as a political response. But, of course, I believe that the Havana Biennial is very important and that we have to save it and other cultural events alike. We have to keep working on creating new, free and inclusive cultural spaces. As long as the dictatorship is alive, I will never be invited to the Biennial. But it doesn’t matter because we are constructing a parallel country.

About copying or doubling something existing: there is a double space present, and both are spaces of resistance. On one side, it is the resistance of everyday life. When we were kids, there were these objects of desire which were not supported by the regime. We knew that Mickey Mouse, Batman, and branded clothing like Nike existed. The system said that they should be banned as consumer goods and US products, so they were not available in the shops. As kids we started reconstructing these objects, for instance by copying the image from the chocolate bar wrappers or copying the branded clothing or creating homemade toys. So it was all imaginary, kind of like an island in the middle of the sea. We sort of created a separate, parallel universe of consumerism.

On the other side, I later incorporated copying famous artworks into my practice. An interesting correlation is that big clothing brands like Yves Saint Laurent or Zara can copy lower culture or indigenous designs, but when these reclaim their copyrights, the companies simply pay them off, and it’s regarded as sorted. But, for example, if you personally copy Nike or Zara, this is not allowed – it’s illegal. So basically, the copying of artworks becomes a space of resistance stating that all these products belong to me too. (There are many people in Cuba who would prefer dressing up in branded clothing to eating proper food.)

#00Bienal is a resistance movement which comes from the desire to create an inclusive institution. The government suspended the 2018 edition of the Havana Biennial, but we said that we can also be the owners of this event and other cultural events, so we organized our independent biennial. It was just another event where we talked about starting from scratch, reconsidering our positions, going back to the roots. We also imagined it for the poor, connecting ourselves to a “third world” mentality to initiate and organize from below and avoid existing infrastructures. We raised questions about copying, about resisting the imposition of a hegemonic model. It is also linked with the idea that the copy of the copy creates something original. So basically, the #00Bienal also pretends to go back to the notion of resistance, like the early Havana Biennials, which functioned as spaces for discussion and criticality. We also go back to the humanistic, socialist ideas that used to sustain the Cuban nation but were lost over time through decades of corrupt politics driven by empty ideology.

Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, from the series Naturaleza Muerta. Convirtiendo la violencia en Arte [Still Life: Converting Violence into Art], February 17, 2021, post from the artist’s Instagram page

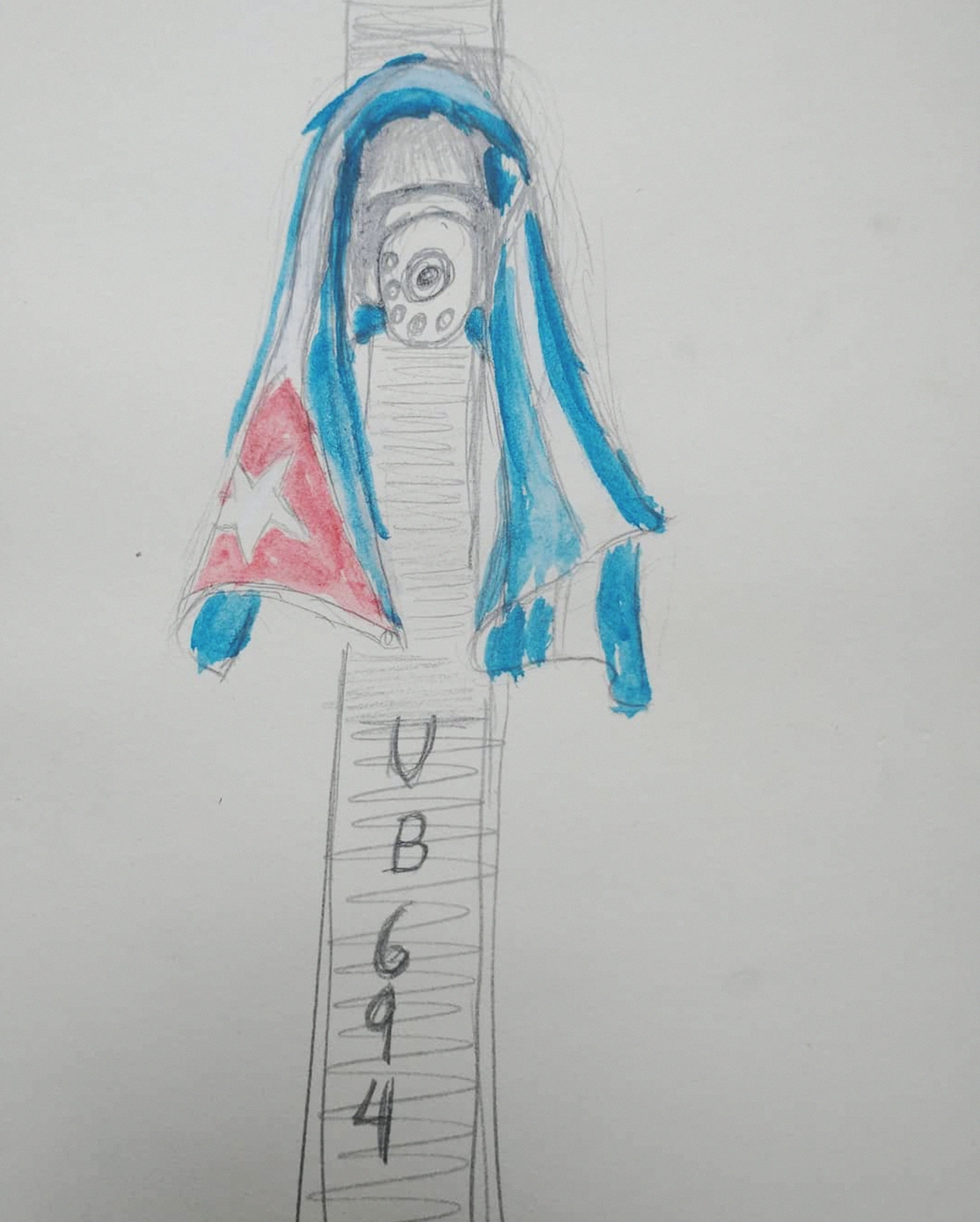

Dóra: Can you describe how the situation has radicalized in the last two years and your position in the process? Along with radical political actions, you have also realized art projects which focus on inclusion and giving new meaning to symbols. The national flag is a case in point. It is of course heavily protected by governmental policies, and the use of the flag by individuals is regarded as an abuse and a provocation. In your actions, it stands for reclaiming national feelings which are not defined by the totalitarian system, and through social media, your actions also quickly spread as memes and garnered international solidarity.

Luis Manuel: As for the flags, the first work was inspired by Daniel Llorente, who ran in front of Raúl Castro on May 1, 2017, with an American flag in his hands and wearing a T-shirt with the Cuban flag on it. For me, this gesture was very brave because it was breaking with nationalism. It was not only brave to run in front of Raúl Castro, but it was exciting to see how he was breaking away from ultra-nationalism, which is captured by the two extremes – the opposition and the extreme Communist Party. He has received a lot of attacks for this act, claiming that he is pro-North America and that he lacks patriotic feelings. It’s interesting to me how the government reacts when sportsmen and sportswomen of Cuban origin start competing for other nations. They blacklist them, calling them anti-patriarchal, non-Cubans. But who are they to tell me who I am and how I should feel about my nationality? If I want to define myself as both North American and Cuban, why should I only define myself with only one nationality? But the regime obviously does not accept these ideas.

So, with my work inspired by Daniel Lllorente’s act, the idea was to initiate a competition to be repeated annually in which young Cubans run with the American flag. Because of this action, I constantly suffer attacks from the regime, and many people criticize me by saying that I am an annexationist or that I love the US above my homeland. In reaction to this debate, I appeared in the public space holding up the Cuban flag for 24 hours. Later, I continued with the artwork Drapo, which also generated a lot of controversy. Drapo is “flag” in French, but it sounds like the Spanish trapo, a cheap piece of cloth. So, what I did was go everywhere, including the toilet, carrying the Cuban flag with me, 24/7. This action also raised several questions: What is your homeland? What direction is it going? Is our homeland a burden? Does it give us warmth? Is it a punishment? Is it something good? All these questions generated more questions in the people who saw or heard about it. Regarding the Bandera todo (the flag belongs to all) meme – it came about as a solidarity action initiated by the San Isidro movement in response to the police putting me in jail for 3 days when I started the action in the public space. So, people started to interact with the flag, drawing it, painting it on their faces, whatever form they found fit the idea. So basically, while I was in jail, the performance continued in this way – people were discussing if the action made sense or not, if there is a homeland or not, expressing their ideas. Even after the regime condemned me on television, there was still an ongoing debate out there about this topic – the flag as a patriotic object.

The law about national symbols here is very ambiguous. For instance, you can see a sportsman or a musician wearing the flag as an outfit, and it is considered OK, but I can’t carry the flag around. So this work questioned this ambiguity too.

Dóra: You have been to jail several times, risked your life with a hunger strike, and you are on a black list and cannot leave the country. How do you see your future? How do you keep yourself together mentally, physically, and emotionally in such demanding situations? More and more young people are joining the resistance – this must give you hope.

Luis Manuel: I’m an artist and not a politician. The Cuban reality is very fractured, with lots of holes and voids. If you initiate an animal protection protest or any other kind protest that brings a mass together to demonstrate against something, people start to come to you and express their appreciation: you are amazing, the best – they make you into a savior. But wait a minute – I don’t want that. I’m just one tool among many other factors trying to change the system.

We are already in the future of Cuba. For instance, we have been talking on Zoom for more than an hour, and this would have been impossible 5–10 years ago. I’m constantly on the streets expressing my opinion, but the regime didn’t put me away in prison for 10 years, which would have happened to an artist 5–10 years ago. The Cuban reality is changing – being more social and taking civic responsibilities is also a change.

Of course, it is exhausting for me. I’m tired. But I’m also tired after creating an artwork which requires a lot of energy. Making this kind of art is complicated. I have to dedicate 60–70 percent of my energy to fighting the system and finding resources to be able to do my art. I'm referring here to mental resources – the resources required to see where I can fit in or fill a gap, to be able to do the art and ensure that the artwork isn't repressed and reaches society and the public. It’s really complicated because we don’t have free platforms. The existing ones are contaminated by the totalitarian regime, and there is a lot of control over information.

With my work, a lot of questions come up, like if I can leave the country, or if they will confiscate my artwork from someone who bought it when they leave the country, or if I will be alive or dead for an exhibition. So it requires a lot of negotiation on the curator’s part. These types of “difficult” artists bring a lot of baggage that needs to be handled because it goes against the system. So, for instance, in this country, a lot of artists help each other by recommending each other to curators and galleries and so on, but in my case, it’s all very “delicate.” They’re not sure as I can bring problems. In addition to handling everything, I need to set aside time to apply for scholarships or events or to network with curators.

Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, from the series Naturaleza Muerta. Convirtiendo la violencia en Arte [Still Life: Converting Violence into Art], February 17, 2021, post from the artist’s Instagram page

Dóra: The title and theme of the planned performance festival in Prague is We Are All Emotional, Have We Ever Been Otherwise? Towards New Gestures of Empathy – how do you relate to the idea of the festival, and what role do emotions play in your work?

Luis Manuel: Basically, the emotion that I would like to transmit is to give an opportunity to others. Like how a small gesture can change things so that another person can have the same opportunities as you. I propose to change the rules of the game from “to win, to come first, or to triumph,” which are also the rules of a patriarchal, authoritarian society.

My idea is to initiate a public chess game. One format is a utopian idea, the other a much more realistic one. The ideal would be to hold a chess tournament in which a lot of players play simultaneously, and the first move is made with a black figure. The fact that black figures come first would modify the whole game and would change all positioning and perspective. So, chess boards and the black figurines playing first, projected onto a big screen where the whole event would be explained. And it would be great if this could turn into an annual event, which would generate a new type of game with the black figures moving first. It would also be ideal if we could invite famous chess players, like Kasparov, so they would participate in this new way of the first move. It would be called F5. The F5 move in chess signifies a peaceful move, not an attack. And F5 on the computer means to reinitiate. And the event would be called the José María Sicre Tournament, named after a black slave chess master. [9]

I also have another idea, which is called “Consumerism”. It comes from my experience when I went outside of Cuba for the first time and went shopping and encountered all the variety of products. How would I know which one to choose? So, I came to the idea that I would enter a shopping mall dedicated to clothing and try on all the clothes that there are in that establishment – try on everything, male and female clothes. So, the performance would be a kind of re-enactment of this.

I would also like to add one more thing regarding the last two years in Cuban reality. Cuban communism is so frozen that only a flower or a child can change it. If you walk around with a flag in another country, it is not a big deal, but here the system is so paranoid that they go after everything that could mean an attack against them. The regime’s concern for the people comes from separation and hatred. For example, if you are religious, you have to reject your family because of that. Or if you have a dissident family member, you have to disown him or her too. Or you have to denounce your neighbor if he has a certain business that doesn’t fit the norm.

People are imprisoned in their own minds. When they see a gesture that changes a bit or breaks something in their dynamic, this might create a movement in the wheel, meaning that it symbolically changes the mechanical structure. It gets greased. If you do something differently, however small that thing is, it looks like a threat to the system, so it immediately turns political. So my artworks or the San Isidro Movement’s actions might not generate a lot of attention or curiosity in other countries, but they do in Cuba, where the regime rejects any opinion that is different. These small acts of difference generate solidarity with others. And our type of art cares for the people who don’t agree with the system. People go where they can receive affection and care, and this is what we offer. We are people that act from love, and our artworks come from love and real worry for the people in the streets. And this is where the system loses against us. This is a revolution of feeling – the aesthetic of feelings. We are restoring a lot of dead connections which were killed by the regime, like interpersonal relations, friendships, or love. These were cut off in the last 60 years. We’re bringing people and ideas closer to each other again.

Conducted via Zoom, March 26, 2021, with the help of Márta Balla translating from English to Spanish and vice versa.

On July 11, 2021, countrywide anti-government demonstrations began in Cuba, triggered by food and medicine shortages which resulted from the Covid pandemic halting all tourism, an industry on which the Cuban economy is to a large extent dependent. Such demonstrations are a rare occurrence, given that the last large-scale protests took place in 1994 in connection with an economic crisis at that time. The current demonstrations were resisted by organized pro-government marches a week later, and any oppositional actions have been violently suppressed by the authorities and the police, with demonstrators taken to prison. At the moment, more than one hundred people are missing. Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, as a regular initiator of civilian movements, was detained again (after having already been held in prison in March and May of this year) before he could join the demonstrations on July 11. He is currently being held at the Guanajay maximum security prison, with no contact with the outside world.

[1] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IYhHjdiq0eE&t=7s

[2] The Hors Pistes Festival at the Centre Pompidou is developed under the direction of Géraldine Gomez. For the 2018 edition, Gomez collaborated with philosopher and dramaturge Camille Louis. Catherine Sicot was invited to include Canadian and Cuban participants.

[3] The informal and horizontally structured school project was founded by Tania Bruguera with the aim to give Cuban artists the training in critical thinking that they did not receive in their formal education. Social and performative art was introduced not only by Tania – she also brought international artists to Havana to make acquaintances with local artists and engage in exchanges with the possibility of critical practices.

[4] In Cuba, state galleries sell artworks and bring the works to international art markets.

[5] As the world grows more connected through the Internet, when artists speak about the realities in Cuba, their words can reach outside the country. Despite the Internet being accessible to everybody on their mobile phones, good connections are still restricted by the government throughout the country. The Internet first became accessible for ordinary people only five years ago.

[6] Rachel Weiss et al., Making Art Global (Part 1): The Third Havana Biennial 1989 (London: Afterall Books, 2011).

[7] https://museodeladisidenciaencuba.org/; https://democraticspaces.com/blog/2020/8/16/the-museum-of-dissidence-in-cuba-2020?rq=museum%20of%20dissidence

[8] José Martí (1853–1895) was a poet, philosopher, publisher, and hero of the Cuban War for Independence against Spain in the 19th century and became one of the central symbolic figures of the Cuban revolution in 1959.

[9] (1817–1871)